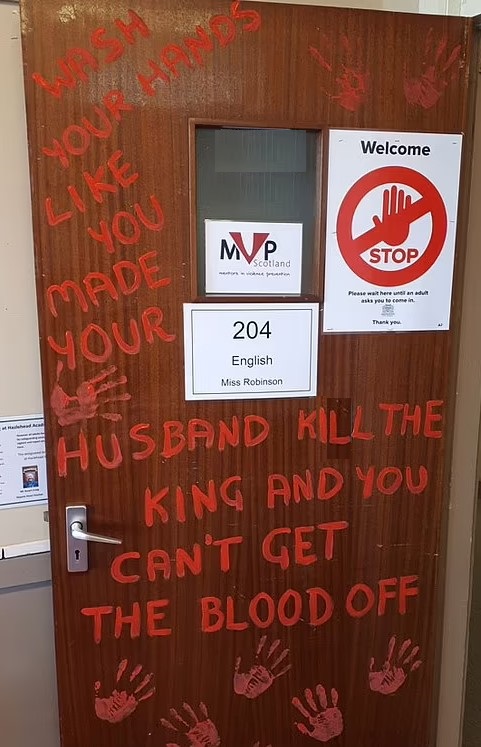

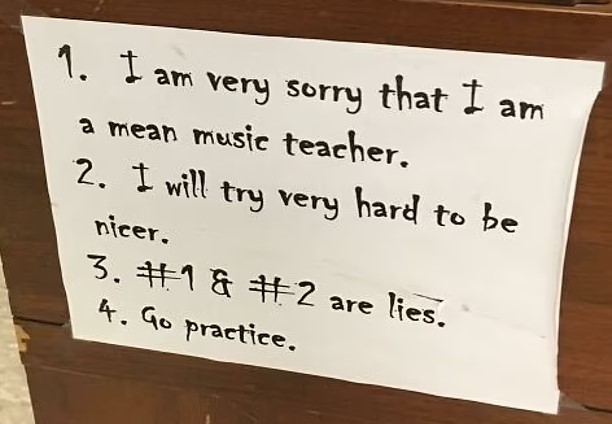

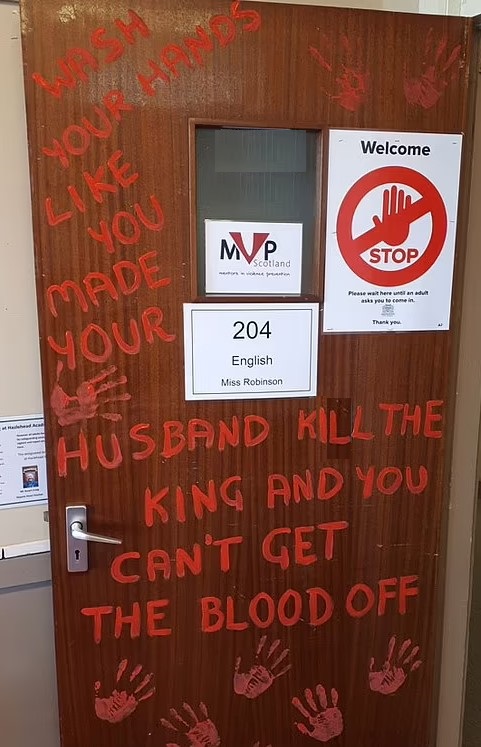

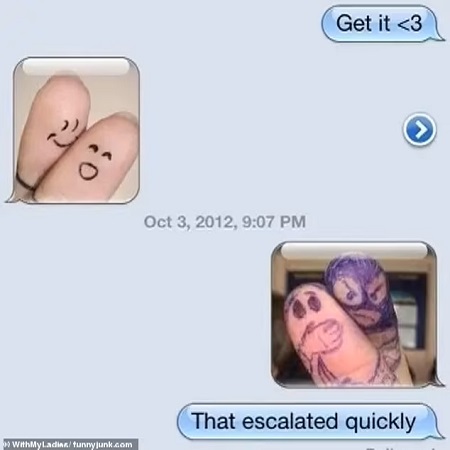

So let’s open the door with some giggles.

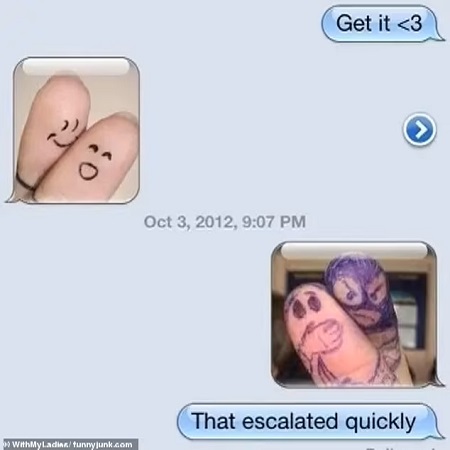

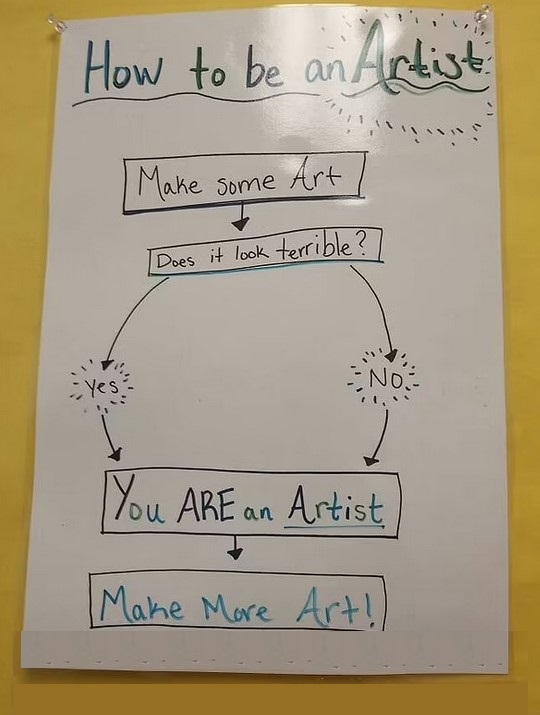

And:

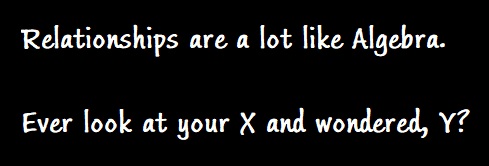

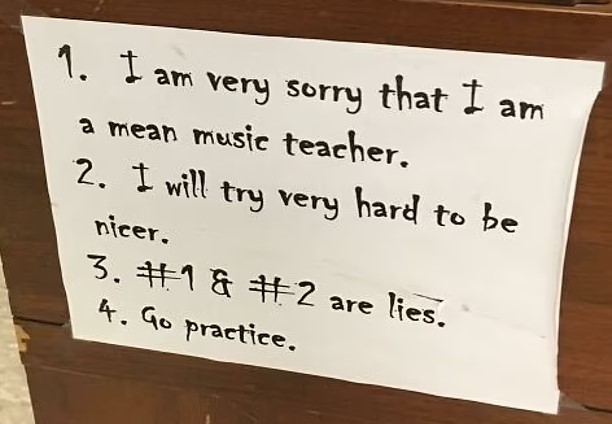

Speaking of bottoms, here are a few:

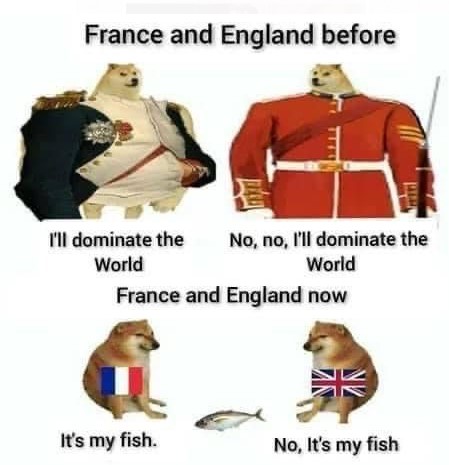

Now get your mind off the beach and go to work.

So let’s open the door with some giggles.

And:

Speaking of bottoms, here are a few:

Now get your mind off the beach and go to work.

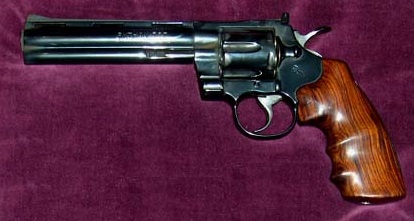

So late yesterday, some asswipe went into a North Texas synagogue, took four people hostage and had some demands.

…because of course it was — actually, only one of Islam’s Finest — and he wanted some other asshole (convicted) terrorist freed from jail.

What happened next?

After a ten-hour standoff, an FBI Hostage Rescue Team made entry and rescued the three remaining hostages. The FBI confirmed the suspect is dead.

My only regret is that the Feebs took the little turd out. Shoulda just left him to a Texas Ranger. (“Only one Ranger?” “Only one asshole.”) Same result, less fuss.

Longtime (and generous) Reader DaleH sends me this call for help:

“I did some genealogy research and discovered my Scottish roots — for better or worse. That sparked my interest and I discovered the world of Scotch whisky. I was wondering about your thoughts on the subject. [quit that laughing — Ed] Single malt Scotch is very interesting and I don’t have to go blind to enjoy it. I suspect you might have an opinion or two?”

Like the title says, I do happen to have the odd opinion or so on the topic.

I first wrote about this topic back in May 2006, so if everyone will indulge me, I’m going to reprint it below as I think it may answer most of Dale’s questions:

I drink Scotch in three ways:

1. Single malts (sipping). Neat, no ice, with a glass of water consumed on alternate sips. This has less to do with style than it does with my frigging gout. I refuse to dilute the lovely stuff in my mouth, but I don’t mind diluting it in the stomach. My favorite single malts are typically from the Speyside region, and I’ll drink pretty much any single malt from those distilleries, but my absolute favorite is The Macallan 25-year-old, with Glenmorangie 10-yr-old as my “everyday” choice. For a “change”, I’ll drink The Dalmore 15-yr-old, which like Glenmorangie is a Highland malt.

Also in the cabinet right now are all the aforementioned (except the Macallan which I finished off a couple months ago [sob] ), plus Glenfiddich 18-yr-old and Talisker 10-yr-old, for those with different tastes to mine. When Mr. FM comes to visit, I usually lay in a few bottles of Laphroiag, his favorite. (Of late, he’s taken to drinking Irish whiskey, but we’re still friends.)

2. Blended (thirst quenching, or at parties). J&B, ice and water — and only J&B. Forget even offering me anything else. No J&B, and Kim drinks something else altogether, like gin. I actually dilute my J&B quite substantially — that gout thing again — and this also allows me to drink for longer periods of time before intoxication sets in.

3. As an after-dinner liqueur. Here I prefer the smoky, peatier singles like Laphroiag or Talisker, because I’m only going to drink one, and I can take my time in the drinking of it.

I’m not a Scotch snob, by the way, even though the above may make me sound like one. My tastes and favorites have come after some fairly extensive errrr trial and experimentation, and like in many areas of my life, I see no reason to change something with which I’m comfortable, and which has come about after considerable experience. I’ve tried most of the major single malts available internationally, and a couple available only in Scotland, but I’ve come to settle on the above because, well, I love their taste.

The wonderful thing about Scotch in general, and single malts in particular, is that it doesn’t matter how you drink it: that distinctive taste will always shine through. (However, I pretty much draw the line at drinking single malt with, say, Diet Coke, because that’s just barbaric — and once you mix any Scotch with Coke, the subtle differences between brands and types pretty much disappear, making the choice of a single malt under those circumstances just pretentious. But hey, if that’s how you want to drink that 40-yr-old Talisker…)

Just be aware that adding water to a single malt doesn’t just dilute the taste, it may change it completely. I find that this is especially true of some Highland malts. Some people happen upon such a taste, and thereafter prefer to drink their favorite single that way. Your call.

Still on the subject of taste, some say that coastal distilleries’ malts are different from those made by inland distilleries because of the salty sea air. I can’t taste it, myself, but I’m not a seasoned Scotch drinker, really.

Finally, it’s a common mistake to assume that the older the malt, the better the whisky. Some malts taste better in their “rawer” state — the malt becomes more bland as it ages — whereas others need the time to “mature” into smoothness. It’s all about your taste and preferences.

Afterthought: It occurred to me that not everyone might be familiar with the Scotch thing, incredible as that may seem. So, for the benefit of anyone who might be interested in pursuing the drinking of Scotch as a career (as so many have), here are a few pointers.

Single malts are the exclusive product of one distillery, made from barley. They will be bottled and sold as such, or else sold to other distillers to be blended with other malt- and grain whiskies (in closely-guarded secret and “proprietary” recipes) to produce “blended” Scotches such as J&B, Haig, White Horse, Bell’s, Cutty Sark and so on.

Blended malts are malts from different distilleries, sometimes called “vatted” malt. (The wonderfully-named “Sheep Dip” is a blended malt. Also, if the brand contains the words “Pride of”, or “Poit”, chances are it’s a blended malt.)

Proprietary (blended) Scotches are also broken into blended grain (grains from other distilleries) and blended Scotch (malts and grains from different distilleries). The actual number of distilleries used can be large, and the actual mix a secret — hence the term “proprietary”. J&B, for example, uses the product from forty distilleries (and almost none from Islay, which is why it’s one of the smoothest Scotches on the market). Johnny Walker Red contains malts from 35 distilleries, and grains from 5 others.

As a rule of thumb, the higher the malt proportion (30%+) in the blend, the more expensive the Scotch. The most expensive (sometimes called premium) blends are at least 40% malt (e.g. Johnny Walker Black, Chivas Regal). The “premium” can also be a factor not of the malt/grain mix, but of the number of malts used — the lower the number of malts in a brand, the more expensive it will be.

Single-grain Scotch whisky is rare (Black Barrel and Loch Lomond being the most famous).

(For all the info on Scotch whisky brands you’re ever likely to need, go here.)

The age of a single malt is denoted by the time it spent maturing in its cask: once bottled, it ceases to age altogether. If you see “single cask” on a single malt’s label, it means it came from one cask exclusively and was not mixed with whisky from other casks within the same distillery. Usually, this variant is hideously expensive, for not much more flavor — we’re well up the curve of diminishing returns, here.

Now for some pointers on the distilleries and their brands. The list is by no means complete (there are dozens of distilleries in Scotland — here’s a map), but I have actually tried all the ones I’ve listed.

The malts differ by region (sometimes by even smaller geographic differences) because of the different waters used, and in the distilling processes. I’ve made a few generalizations, however, just to give people an idea.

One last note: when you see a “The” before a single malt’s name, it’s not generally an affectation. Sometimes, the name is an area, not just an actual distillery (eg. Glenlivet), and “The” is usually added to denote either that it’s a single malt, or that it comes from the distillery of that name.

Speyside whiskies have a smoother taste, lighter flavor and softer aroma than most other Scotches. They are distilled, as the name suggests, in distilleries which are found along the River Spey on the northeast side of Scotland. Some of those distilleries (there are at least twenty major ones) are: Knockando, Glenlivet, Aberlour, Balvenie, Glenfarclas and Macallan.

Island/Islay whiskies come from the islands on the west- and north coasts of Scotland. Typically, they are much heavier, more aromatic, peatier-flavored whiskies, and some of the distilleries are very well-known: Laphroiag (la-froy-yag, from Islay), Talisker (Skye), Ardbeg (Islay), Highland Park (Orkney) and Bowmore (Islay).

Highland whiskies come from the north of Scotland (sometimes split into northern and southern Highlands). They tend to be darker than the Speyside malts, but not as peaty as the Island ones. Brands include such names as Dalwhinnie, Glen Ord, Dalmore, and Glenmorangie.

Lowland whiskies come from points around the Edinburgh – Glasgow axis, and there are really only two major ones: Rosebank and Glenkinchie (which is the main ingredient of Dimple Haig). I’ve tried Rosebank and didn’t really like it that much, but others (not put off by the “Lowland” appellation) swear by it.

Some factoids:

What amazes me after 15 years is how little my opinions have changed on the topic. But that’s pretty much true about everything, really. A few examples:

Still my favorites, after all these years…

I’m not going to argue with the genius of Juan Trippe, the late head of Pan Am (as discussed in last night’s homework assignment). But the problem with genius is that it can overstretch itself, which is what happened to Trippe, and that had dire consequences for Pan Am.

But first, it’s time for yet another one of Kim’s Supermarket Stories (and I promise it has relevance).

I once worked for a chain which prided itself on the quality of its product — not only the merchandise, but the service of its customers. The Produce Department (Fruit & Veg to non-Murkin Readers) was as good as any “street market” or “farmer’s market”, for the simple reason that the store merchandisers tossed out a tremendous amount of any produce items which they judged sub-standard or even close to going “off” before they ever set it out on the shelves, in the bins, fridges or displays. The result was that you could pick any item off the display stand, and had no need to check it because you just knew that it had passed a stringent quality test. And the same was true of every department: (on-site) bakery, meat department, deli and so on. As a result, our average basket cost a little more than our competitors’, but then again, our typical shopper belonged to a higher income bracket: the kind who value quality over price and expect the best. Our average household, therefore, usually consisted of a high-earning husband/wife with teenage kids, who lived in the upper-middle class suburbs where (surprise surprise) 95% of our stores were located.

I was at the time the senior marketing manager for the chain — ran the loyalty program, worked with the Advertising department, worked with Purchasing on product selection and so on.

Then we had a huge management change: new CEO, new COO and new CFO. When I went to the first “welcome” meeting, the new CEO announced, without any fanfare, that our chain would henceforth be aiming for the lower segment of customers: younger moms with small kids, more “efnic” shoppers, and so on. After the meeting, I managed to get a one-on-one with the new CEO, and blew up at him.

To his credit, the new CEO didn’t fire me on the spot. But his lofty answer was that the board of directors had decided that we needed to “grow the business”, and as we had the upper end of the market more or less to ourselves, we needed to expand our customer base.

Which brings us back to Juan Trippe and Pan Am.

It’s clear that Pan Am had a quality product, and their clientele were not people who, let’s say, were at the bottom of the market. Their service was unparalleled, not only in the airline industry but anywhere, and it showed in all aspects of their business: hiring, training, equipment and cuisine.

Then Juan Trippe decided to “grow the business”, and open Pan Am up to the lower end of the market via mass-market people carriers like the Boeing 747.

I had always wondered why Pan Am ever, or could ever, have gone out of business. The YouTube video gave me all the answers. To be blunt, Pan Am went from “You can’t beat the experience… Pan Am!” to “We’re just another airline; check out our low prices.”

Their demise was as predictable as that of the above supermarket chain: both went out of business only a few years after making that calamitous decision to chase a new market.

Side note: I resigned a month after my meeting with the CEO.

Now, had I been Juan Trippe and wanted to “expand the market”, I would have done a couple things differently.

That’s the basic idea of the thing, but you get my drift. It might not have worked and Pan Am might still not have made it. But they failed anyway, so how much worse could the outcome have been?

But at least they wouldn’t have screwed up their Pan Am brand, which was priceless. And the actual blowing up of the Pan Am brand was the entire responsibility of its founder.

Your homework for this evening is to watch this movie.

Of course, it’s not compulsory, but if you don’t, then tomorrow’s post will make little sense. So it’s up to you.

You can’t beat the experience…

I know that politicians are completely ignorant about everything not political or legal — and even then, they’re not especially bright — but Elizabethan ignorance on everything can only be truly appreciated by acknowledging her academic credentials. [/snark]

Even by her own heritage of ignorance, however, Elizabeth Warren’s latest broadside against Big Grocery must rank among her greatest cock-ups.

“What happens when only a handful of giant grocery store chains like Kroger dominate an industry? They can force high food prices onto Americans while raking in record profits.” Warren claimed that “a handful of giant chains” had replaced the wide selection of smaller stores that used to dot the American landscape, and she called for the use of the government’s antitrust power to “break up these giant corporations.”

Ah yes… let’s blame an industry for price gouging — an industry that traditionally runs on 0.75% net profit margins.

Remember, by the way, that while I know a few things about some things, and almost nothing about a whole lot more, when it comes to the supermarket business, I know everything about it. That’s not a brag, nor even an exaggeration; it’s what comes from close to a third of a century of experience in and around the industry.

So hear me now when I saw that Reason Magazine’s Joe Lancaster has it exactly right:

In actuality, for much of the last year, grocery stores have seen enormous boosts in revenue, but not increased profitability, for the simple reason that everything has been costing more: not just products, but transportation, employee compensation, and all the extra logistical steps needed to adapt to shopping during a pandemic. Couple that with persistent inflation—which Warren also recently blamed on “price gouging”—and it is no wonder that things seem a bit out of balance.

She is clueless, a fraud and incompetent. All she has is Marxist dialectic by which to formulate her idiotic positions on every topic under the sun — dialectic which when translated into policy has boasted a record of 100% failure — and the sooner the citizens of Massachusetts vote this moron out of office, the better the country will become.