Once upon a time, I worked for a Great Big Research Company — no name necessary, but let’s just call them A.C. Nielsen, because it’s easier to type “Nielsen” instead of “Great Big Research Company” — and the department I worked for was called “Trade Relations”.

A little background is necessary here, before I continue. Most people, when seeing the name, think of the Nielsen Ratings as pertaining to TV. In fact, that division of the company was only responsible for about 20% of corporate revenue, when I worked there. The vast majority of revenue came from providing market-related information to the manufacturers of consumer packaged goods (CPG) manufacturers like Proctor & Gamble, Kraft Foods, Unilever, Heinz Foods, S.C. Johnson, Pepsi-Cola and so on. (Nielsen actually coined the term “market share” when Arthur Nielsen founded the company back in the early 1920s.)

Basically, the concept was simple: how much product was being purchased by consumers at any given time? One would think that manufacturers would have had a good idea of this, based on their own shipping data, but they didn’t, for all sorts of reasons. For one thing, retail outlets like Kroger or Safeway would buy a lot more cases of product than they actually needed at the time and warehouse it, both to make their own resupply of their stores more efficient and to lock in prices in case of future increases (known as “forward buying”).

In fact, most manufacturers had no clue how actual consumer sales were faring for their products. What Nielsen did was approach the retail chains and get access to their sales data (either through outright purchase or by auditing a representative sample of stores), assembling the data into huge databases and then creating monthly or bi-monthly reports which the CPG manufacturers would purchase. So when the manufacturers approached the retailers and talked about pricing and delivery, both sides of the table would be talking about the same data and negotiations would be comparatively cordial, in theory anyway.

Obviously, for such a system to work for Nielsen, there had to be a good relationship with the supermarket chains, hence the existence of the “Trade Relations” department. What we did, therefore, was collect the data and, in the form of account executives like myself, relay market-level data back to the chains’ executives. Because while the chain would know how much they had sold of a product to consumers, they had no idea of what their competitors had sold of the same, and therefore had no idea of their own market share.

In many cases, Nielsen was able to leverage the value of that retailer’s information against the cost of the data, which is where people like myself were critical: the quality of the reporting was of great value to the retailers’ marketing and merchandising departments. Several large chains admitted, privately, that their business plans would have been not only more difficult but almost impossible without the reporting supplied by Yours Truly and his compatriots. For a free service, therefore, it was a no-brainer.

All went well until Art Nielsen Jr. (son of the company’s founder) sold out to some evil bloodsucking company of debt collectors (Dun & Bradsomething) whose accountants, after a couple of years, decided that we in Trade Services were providing such a good service to retailers that the retailers should start paying for those services — which, as we know, had hitherto been free. The result of this little corporate reindeer game was twofold: the retailers told us to fuck off, and I resigned and went to work for a Great Big Advertising Agency instead.

I told you all that so I could tell you this.

I have often railed against this trend of “convenience”, made ineffably worse by the age of electronics and most recently, by the Internet of Things whereby activities that required even the slightest effort can now be ameliorated or eliminated by having remote access to said activities.

Chief among these, of course, are things like programmable refrigerators, remote starters for cars, and of course Satan Amazon’s Alexa.

And as I have also said before, the very nature of these things involved giving something — or to be more specific someone — access to your appliances, vehicles and lifestyle. While I joked about some asshole kid in the basement of his mother’s house in Schenectady being able to hack into your network’s system and turn on your stove to get your house to burn down, I can see now that making a joke of the situation — in hoc reductio ad absurdam, so to speak — was not helpful.

What is more malevolent is that someone actually inside your personal network — i.e. the provider of a service — can start to affect your life, and in ways that are not always to your advantage.

The specific case in point is this trend of auto manufacturers (step forward BMW, you bloodless Kraut assholes) to take electronic conveniences included in your car and start to levy a fee to continue the features’ usage. Your reversing camera — a great safety feature, by the way — would suddenly become inoperable unless you paid a “nominal” (say, $19.99) monthly fee to BMW.

In other words (and this goes back to my experience in the supermarket business), what you used to get for free as part of your purchase would suddenly involve a cost.

Now we could all probably live with unheated seats, for example, or having to use a key to start the car’s engine instead of starting your car with an electronic fob (also, by the way, easily hacked by thieves). But the thought of having to pay some monthly pound of flesh to Big Auto for features that were supposedly included in the (already bloated) purchase price of your car should make one want to resist such a change.

The legality of such manufacturers’ initiatives is discussed by Internet lawyer Steve Lehto — the link sent to me by Longtime Reader Mike L., thank you Mike, and which gave rise to this whole rant. And yes of course one can discuss legalities all day, except that the minute one does, one has to involve both lawyers and politicians (considerable overlap), all to deal with a situation that should fall under the concept of “doing the right thing”, but which in modern times seems to have gone bye-bye like so much else, and particularly in the case of Global MegaCorp Inc. and their fucking accountants (who, make no mistake, are the driving force behind this bullshit just as the Dun & Bradstreet accountants were behind the initiative which drove me from A.C. Nielsen).

What’s worse is that I don’t know if this wave of bloodsucking bastardy can even be slowed, let alone halted or reversed. Certainly, if one is going to purchase a car from Global CarMaking Inc., resistance will be futile because they hold all the cards (and especially the politicians) in their sweaty little accountants’ hands, and the increase in corporate profitability will be cheered to the rafters by their shareholders — who, lest we forget, are largely composed of other big companies like retirement funds and such, as well as politicians (don’t get me started).

And “the market” is unlikely to come to our assistance either.

Oh sure, one could always buy an ancient vehicle which does not hold all the electronic doodads which make this corporate fuckery possible, or else a “stripped down” vehicle like, say, a Caterham which is bare-bones driving incarnate:

…until, of course, the Gummint passes legislation which outlaws the ownership of older cars or trucks (because of “environmental” concerns) or of stripped-down cars (because they don’t contain sufficient “safety” features).

And if you think that Congress wouldn’t dare to pass such legislation, you obviously haven’t been paying attention because that’s precisely what they’ve been doing for the past half-century.

Of course, this isn’t just confined to the U.S.A.; it’s already a going concern in Europe and the U.K. (ULEZ, anyone?). So the steamroller is well on its way, and you’re the one staked out in its path.

Have a nice day.

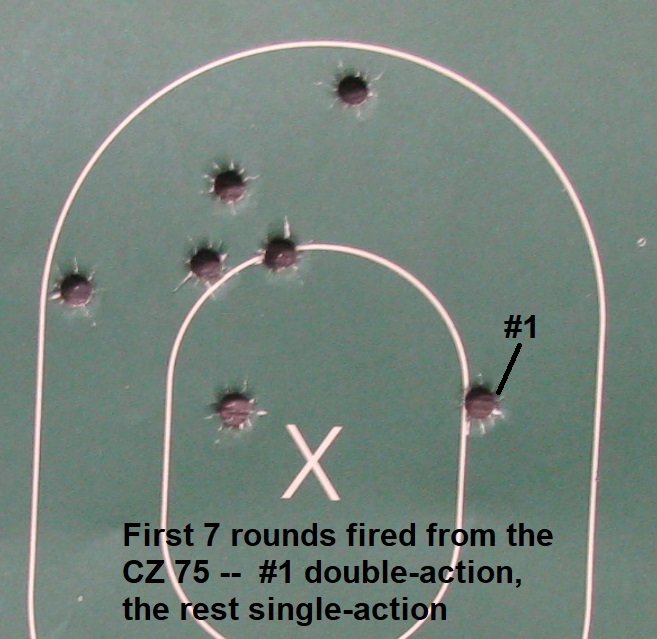

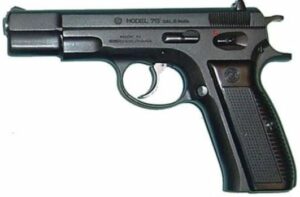

Me, I think I’ll go to the range.

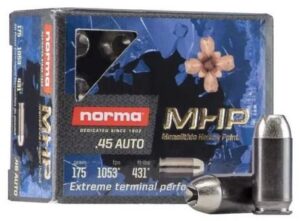

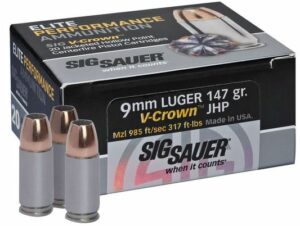

…because that was the cheapest ammo of those specs I could find.

…because that was the cheapest ammo of those specs I could find.