Aaah, tattoos… or as I prefer to call them, body graffiti.

I have two major points to make about this topic.

The first is that I think that the acceptance of tattoos is yet another sign of the coarsening of our society and its growing decadence. If we look at who’s sported tattoos on their bodies in the distant past, it’s been primitive tribes attempting to make their warriors look more fearsome (e.g. Maoris, Amazon tribes), or else the womenfolk of the tribes trying to make themselves look unappealing to men once they were married / paired off permanently, or else all members of a tribe wearing the same markings as a symbol of identity, to distance them from members of other tribes. Regardless of why, however, the common aspect of all was that these were the actions of primitive peoples. So now it appears that because tattoos have become somehow “cool” or tokens of individuality, we as a society have to accept them. After all, nobody gets hurt, right? (I’m leaving out the tragedy of infection and so on, because that’s relatively rare nowadays.)

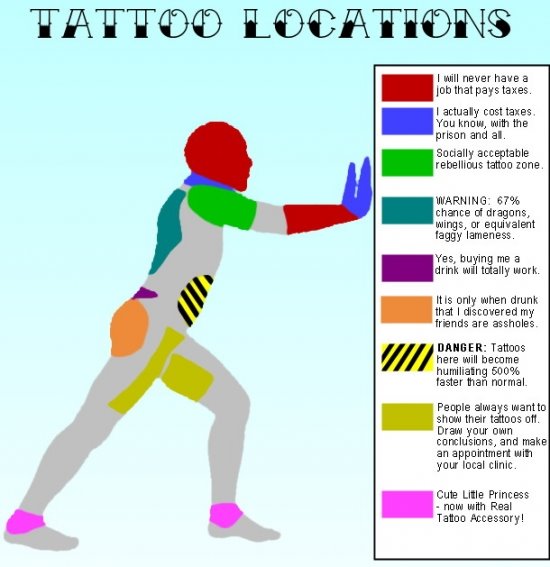

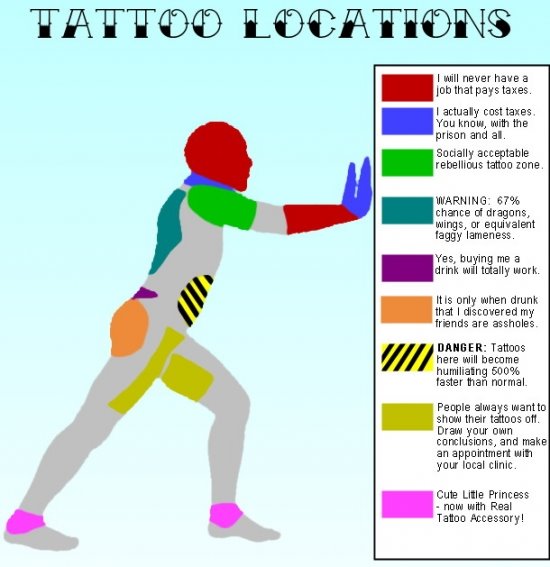

My other point is personal, so buckle yourself in, because this is going to be a bumpy ride. To start with a humorous take, here’s a little guide to tattoo placement:

I’ve never really understood tattoos as decoration. Maybe it’s because I was brought up to believe that only low-class types got tattoos: they, sailors and strange Asian people. However, it seems that nowadays just about everyone has them, except for every woman I’ve ever dated — it’s an immediate disqualifier for me: no matter how small, how discreet or how “tasteful”, ink on a woman’s skin = Kim moving in the general direction of away. I can understand why men get tattoos, because we’re idiots and do stupid shit all the time — not excusing, just understanding — but I see no reason why a woman should ever deface her body, for any reason whatsoever. (Yeah, I’m pedestalizing, to use that horrible modern term. Sue me.) Even stuff like this, while undoubtedly artistic and aesthetically pleasant to look at, occasions from me at best a disgusted curl of the lip when I see it in (or on) the flesh. On silk, it’s beautiful; on a woman’s skin, repulsive.

Then, of course, you get outcomes such as this one, which turns an already-trashy-looking girl into a vision of pure horror:

You just know she’s got a “tramp stamp” at the base of her spine. (My take on tramp stamps: regardless of the design or verbiage, what they’re all saying is: “Insert Here“.) Don’t even get me started on tattoos around the vulva… ugh.

I’ve also never understood why a beautiful woman would get a tattoo. (Ugly ones, sure: why not? You’re already ugly.) A good example would be Britain’s Got Talent judge Amanda Holden. Unquestionably, a lovely woman:

Inexplicably, she has two (!) tattoos. “Yeah, but they’re not visible, Kim!” Well, except (and one hopes, only) to her husband. Seems kinda pointless to me, especially for a woman who seems to have everything in her life under control. (But I’ll get to that later.) Then you get this neurotic bint, who says that older women getting a tattoo means that “they still have something to say”. Yes, and that something is: “Getting older doesn’t necessarily mean getting wiser.”

Of course, my ire is not just aimed at women. David Beckham, supremely-talented footballer and canny businessman, has turned his once-handsome body into some kind of freak show:

Jesus wept. (Literally: see bottom-left corner.) I know: footballers are generally low-class scum (also musicians, another massively-tattooed segment of the population), but even for scum, Beckham’s taken it A Picture Too Far (or several pictures too far). (For my Lady Readers, here’s Beckham, pre-body-decorations:)

Note, by the way, that he’s wearing a shirt to cover up some of his arm tattoos. That was the manufacturer’s marketing department, not wanting to alienate the average consumer.

When it comes to men, I sort of get the “bonding” rationale — “Semper Fi”, “U.S.S. Arizona”, “Rangers Lead The Way”, and even “Harley-Davidson” and so on. I also get the “commemorative” ones: “Bagram AFB 2015”, “Bastogne 1944” etc. I don’t agree with the rationale, but I get it. But as for examples like Beckham’s? Sorry, I got nothing. I just ascribe it to “Men Do Stupid Shit” and move along. (And please spare me the “bad boy” bullshit. Real bad boys don’t advertise; and women who get taken in by that deserve everything they get, e.g. hepatitis C.)

Here’s how I approach the whole issue. If I were going to get a tattoo, I say to myself, what would it be? What would I want to immortalize on my skin?

Right off, I can eliminate messages, sayings, or any verbiage whatsoever. I can think of no saying or statement that would qualify as worthy of being on my body, forever. “Mother”? Give me a break. If I’d ever got one of those idiotic things, my mom would have killed me. Yeah, you love your mother. Me too. Everybody else too. BFD. And as for those “affirmation” expressions: “Love Is All”, “Strength Through Willpower”, “Keep Believing” (in what? God? yourself? the Chicago Cubs? a Doobie Brothers reunion?”), and my All-Time Bullshit Message: “No Mercy”… really? You’re that much of a bad-ass that you have to advertise it? It’s “message” body art by Hallmark, except Hallmark would never create crap messages such as these. I also love the ones which feature Chinese or Japanese pictograms, and laugh like hell when the hapless recipient discovers that the tattooist has actually written “Idiot Gaijin” or “Won Ton Soup” instead of “Mighty Warrior”, as requested.

And then there’s the stupefying array of crucifixes. Yeah, I bet Jesus is SO proud of you. Why don’t you just wear a simple crucifix on a chain around your neck — it says the same thing, is less painful / expensive, and as a bonus, you don’t look trashy. If it comes to Christians like this, give me an Orthodox Jew any day. (Tattoos are forbidden under Talmudic Law as something like “defiling God’s creation”. No truer words were ever written.)

The problem is, when we think of images to be tattooed onto our skin, we fondly think they’re likely to look beautiful and artistic, like this:

…when the odds are better that they’ll instead come out like this:

You know, that last pic actually makes me feel nauseated. Imagine that woman serving you food at a restaurant… and yes, I have asked to be moved to another table featuring a non-sleeved waitress (Kirby Lane in Austin, TX).

And I note that tattoo reversal is becoming HUGE business in Japan, because companies are finding that employees with unmarked skin tend to be better at their jobs — less absenteeism, better attitude, more reliable — and are therefore refusing to hire people with visible tattoos. Just sayin’.

I remember doing one of those foul “speed-dating” things once, back when I was a single guy. My very first question to a prospective date was: “So… tell me the story behind your tattoos.” (There’s always a story / excuse.) Any response which wasn’t “I don’t have any tattoos!” meant she had no chance with me. More than half the women I spoke to were tattooed, sadly, so I didn’t bother with the speed-dating thing again. And for the record: I have never slept with a woman who has a tattoo. Won’t ever, either.

Here’s my final take. With only a few exceptions, I think decorative tattoos — especially comprehensive ones like full-body or sleeves — are indicative of some mild form of pyschosis. There is a peculiar strain of either narcissism or self-loathing involved, and (paradoxically) maybe both. Whatever it is, I’m not really interested in trying to understand it.

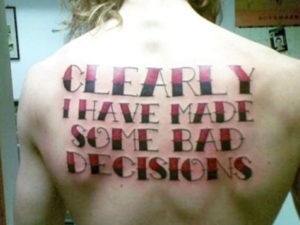

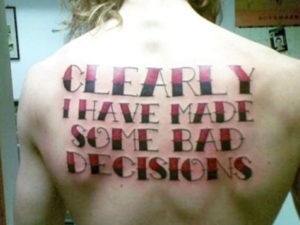

Yup. You call it “clever-ironic-witty”, I call it confirmation.

———————————————————————————

Afterthought: I’ve probably pissed off a sizeable number of people with this post. I don’t care. If you are thus defaced, know that there’s a considerable proportion of the population who feels exactly the same way as I do — and as I always say, if you’re going to deliberately set yourself apart from polite society, don’t be surprised when you’re treated like a pariah. Or maybe that’s the point: “I’m a rebel!” Yeah, you and all the other people with tattoos. Repeat after me: “We’re all individuals!”

Yeesh.