This one got my attention, so up it goes:

It’s funny: you think it’s just a rendition, and then you go to London’s King’s Cross or the Gare du Nord in Paris on a chilly misty morning… and it looks almost exactly like that.

This one got my attention, so up it goes:

It’s funny: you think it’s just a rendition, and then you go to London’s King’s Cross or the Gare du Nord in Paris on a chilly misty morning… and it looks almost exactly like that.

Whilst scouring the very bowels of Teh Intarwebz I came upon this picture, which immediately became my wallpaper:

Right-click to embiggen.

Over at Intellectual Takeout, John Horvat talks about bananas on walls:

My reasoning centers on a recent event in New York City in which the renowned Sotheby’s auction house sold a 2019 art piece dubbed “Comedian” by Maurizio Cattelan. The work consisted of a fresh banana duct-taped to the wall.

The bidding started at $800,000, and within five minutes, the item sold for $5.2 million plus auction house fees, which came to a total of $6.2 million. The new owner is Chinese-born crypto-businessman Justin Sun.

The actual banana cost thirty-five cents when bought in the morning at an Upper East Side fruit stand. The new owner will get a certificate of authenticity and installation instructions should he want to replace the banana before it rots. Mr. Sun has already announced that he will eat the original banana “as part of this unique artistic experience, honoring its place in both art history and popular culture.”

Commenting after the sale, Billy Cox, a Miami art dealer with his own copy of “Comedian,” says the work is something of historical importance that comes only “once or twice a century.”

Uh huh. Like the paint-splattered “art” of Jackson Pollock, to describe this as “art” at all, let alone something of “historical importance”, is to underline the folly of the so-called cultural elites and their absurd mania for post-modernist deconstructivism.

We are living in a society where certain liberal sectors inhabit an alternative reality where thirty-five-cent bananas are handled as multimillion-dollar works of art. The problem is that they want to force everyone else in society to believe their madness.

“Pull the other one” would be the obvious rejoinder. But Horvat takes it further:

The first are those who do not want to see the absurdity of the banana on the wall and dogmatize that it is art. They create their own reality and impose it on the nation.

The second group consists of those tired of being told a banana taped to the wall is art. They long to live in a world where art is art and bananas are bananas.

In the [2024] election, some of the latter group said, “Enough is enough.”

This reaction was not against a single banana on one wall.

You see, there is [also] the banana that claims a man is a woman and a woman is a man. Other bananas claim that people can choose their pronouns, pornography in libraries is literature, or that it is just fine for men to compete with women in sports. We are told drag queen story hours are suitable for children, after-school Satan Clubs are educational and it is not a human baby but a clump of cells.

It is all part of a vast banana extravaganza that we are asked to admire and make believe is the blueprint for a dream society.

Quite right. There’s only one thing to do when faced with these bananas:

yup. Dip them in boiling oil.

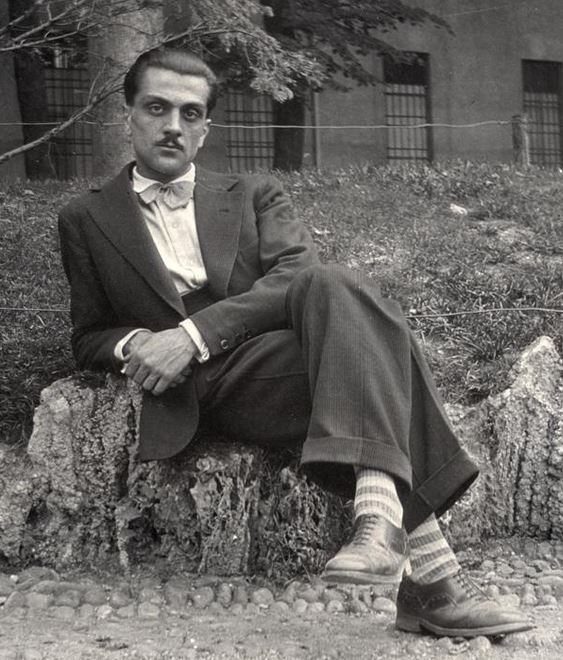

What do you call a man who was a professor of Architecture at Turin University, photographer, writer, skier, inventor of engines and designer of race cars, acrobatic pilot and mountaineer? Carlo Mollino.

I have to say that I’m not enamored of his exterior architecture designs — there’s way too much Gropius and not enough Athens, never mind art nouveau;

…although not all the time:

His interiors are a little too Scandi and not enough Edwardian:

…although his Teatro Regio in Turin is incredible:

…from the inside; the outside?

…and of his furniture we will not speak.

(Follow the link above for a full exposition of all these, and more.)

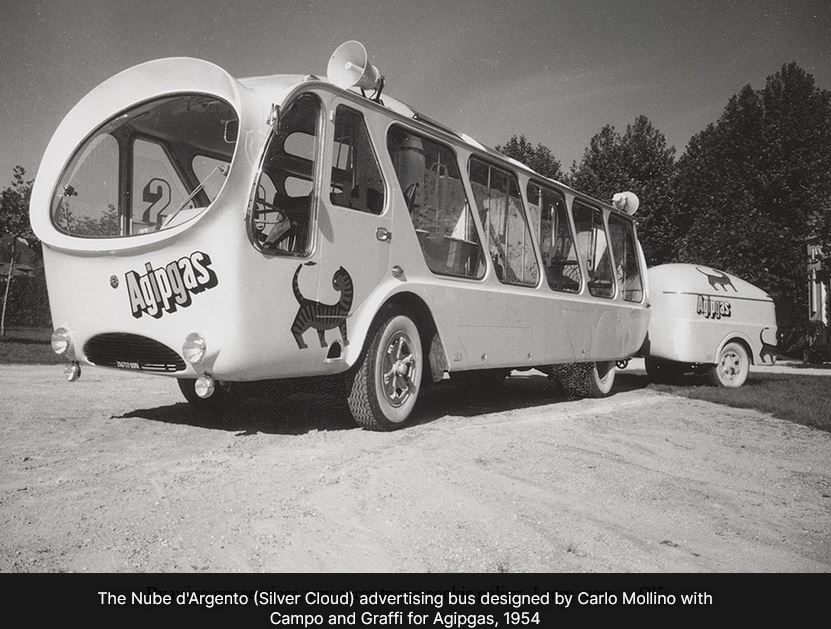

But how can you not enjoy his design of something as mundane as a bus?

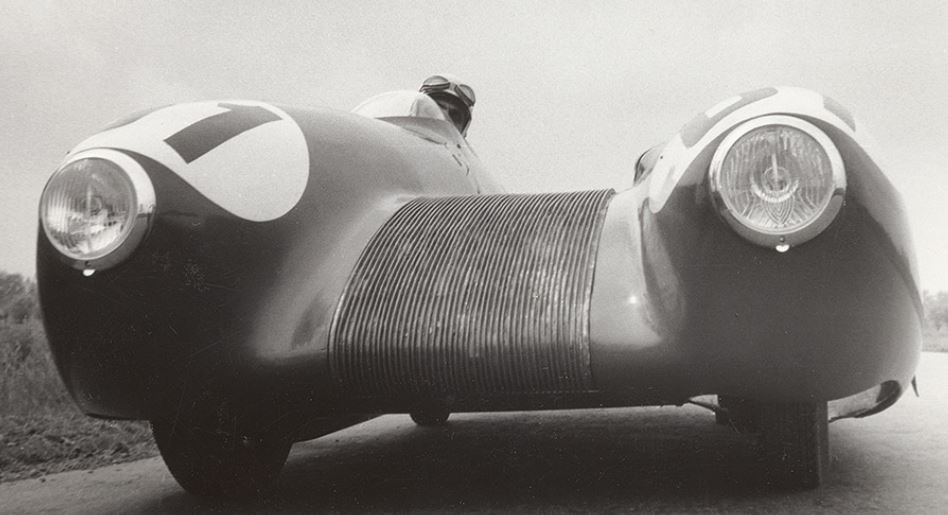

And then there was his Basiluro race car, which at Le Mans 1955 (yes, that Le Mans race) managed to reach 135mph with a 750cc engine (!) until it was forced off the track into a ditch by a Jaguar:

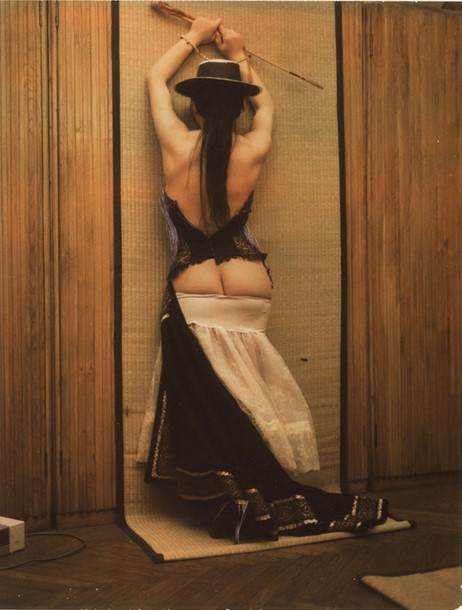

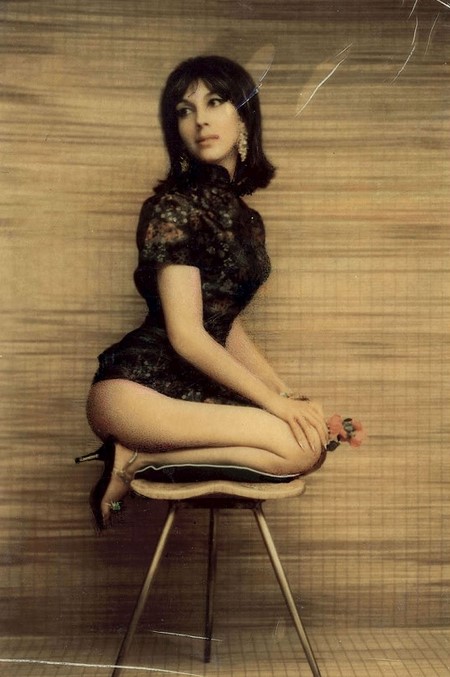

However, it was Mollino’s photography which first caught my attention (guess why):

And my favorite:

His ultimate expression was this statement:

“Humans matter only insomuch as they contribute to a historic process; outside of history, humans are nothing.”

And Carlo Mollino sure left his mark on the historical process, in so many fields. Che uomo!

“Today in the art world, anything goes but almost nothing happens.” — Roger Kimball

By all means, read the whole essay.

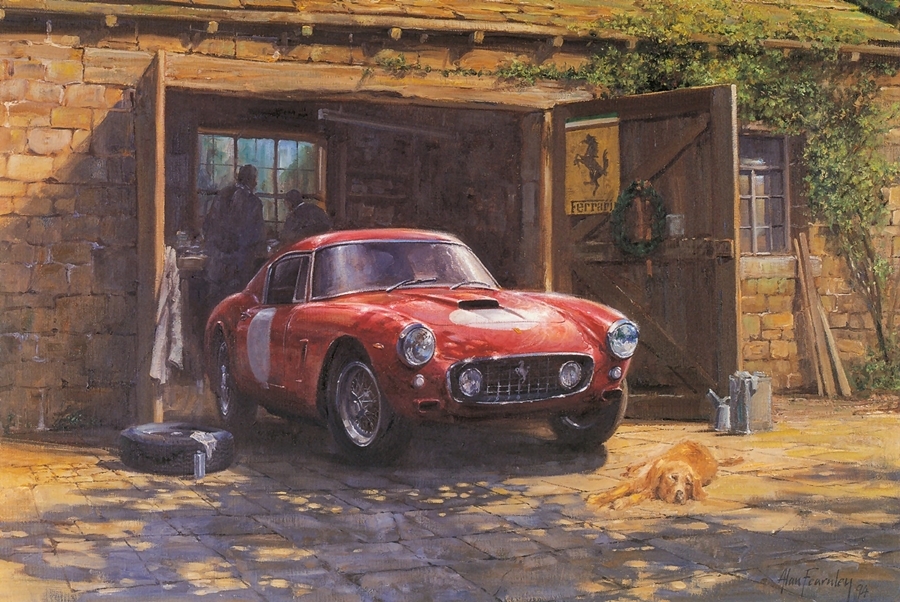

I’ve been in a Ferrari State Of Mind recently — no idea why, it’s just there — so for the past two weeks my laptop’s wallpaper has been this one:

Yup, it’s Alan Fearnley again.

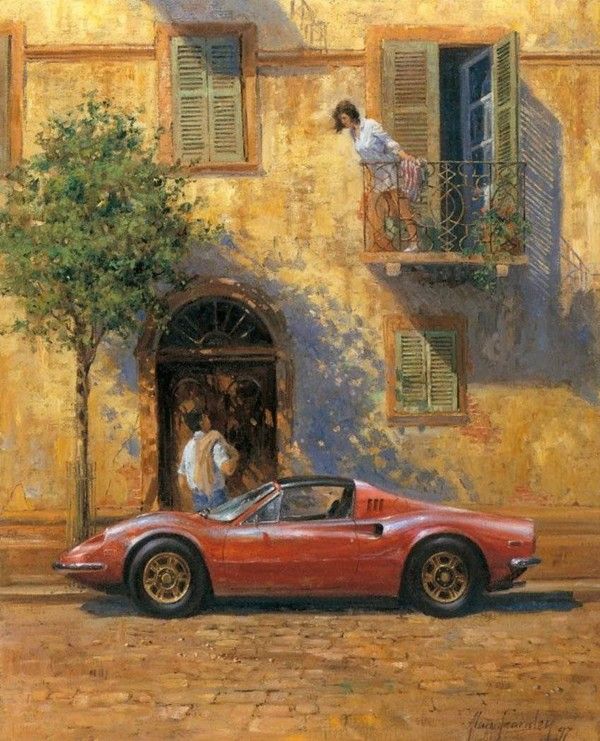

Anyway, I decided to make change, but the Scuderia thing was still strong, so:

“Why do you keep me waiting, cara mia?”

“Just two more minutes, I promise.”

I love this picture.