This phenomenon doesn’t really occur in the United States because schoolboys don’t wear ties. Okay, I joke: it’s because school affiliation in the U.S. happens at university rather than in high school (but they still don’t wear ties).

Here’s how the thing works among the private school set, and it’s true in Britain and all its former colonies (in Britain, they’re called “public” schools, which is massively confusing to non-Britons so I’ll just use “private”, to be consistent). To be sent to an exclusive private school was a sign of both wealth and breeding (the latter more so in Britain than in the colonies, of course). The bonds one formed at school, in an age when a university degree was not a prerequisite for employment, would help one through life in no uncertain terms, because one always tried to help a fellow private schoolboy (called an “Old Boy”) where one could.

The reason for this was quite simple, and understandable. If a manager, an Old Boy from St. John’s, say, discovered that a prospective employee had been to Michaelhouse or Bishop’s, the applicant would automatically get a more favorable review than someone not wearing the old school tie: Old Boys were essentially a known quantity, having been through pretty much the same grinder that all the others had. As any employer will tell you, a known quantity is almost always better than an unknown one — a former U.S. Marine will favor another Marine for precisely the same reason, and it has to do with character rather than anything else. One of my former classmates owns a highly-successful tech company, for example. and it came as no surprise to me when I learned that his CFO was yet another of our classmates. No chance of financial skulduggery there, I bet. Unthinkable.

I once got a job because the H.R. manager saw my Old Boy’s tie and after chatting about the school for a while, she sent me off for a final interview with my future manager with barely a question. (She gave me a sealed envelope for him, and he showed it to me much later. It read simply, “Hire this man — he’s exactly what we’re looking for.”) It turned out that the H.R. manager’s young son was at St. John’s Preparatory, so she knew exactly what kind of man I was, because she wanted her son to become the same kind of man. My First from St. John’s College. along with a couple of other notable schoolboy achievements, were all she needed.

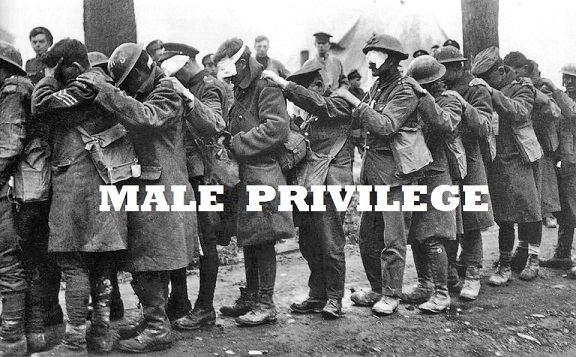

This causes all sorts of problems in today’s oh-so egalitarian society, but if we’ve learned nothing else over the years, it’s that when it comes to leadership, character matters. By the middle of the First World War, St. John’s had graduated just over one hundred and twenty boys in its history; twenty-two ended up killed on the Western Front, and one (Oswald Reid) won the Victoria Cross (posthumously). The death toll among Old Etonians, Old Harrovians and their like was equally appalling, because it was from the private schools that most of the officers were drawn. Yes, it was part of the class system; but it was also true that leadership was one of the virtues taught and encouraged — and it had been duly noted by the Duke of Wellington in a much earlier war, who said that “the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton.”

And he was right. Character matters, and it seems to be that because of the harsh regimen of private school education in the past, it was inculcated as much as Latin, Greek or the Classics — and possibly even more so, because up to my time, one of the worst insults you could bestow in someone was that they were a “swot”, someone who worked hard at their studies. A “gentleman’s C” was highly regarded because it meant that one had achieved a passing grade without working too hard at it. (I should also point out that academic standards were far higher then than they are today, and a “C” back then would today equate to a B+ or even A-, depending on the subject.) I remember winning some award in a magazine for an essay I’d written, and there was considerable amusement when it was discovered that my English teacher had given me a grade of 68% (27/40) for that same essay. When he was asked about it, he shrugged and said, “His conclusion wasn’t that good.” Nobody got an A in his class, ever, so strict were his standards. What that meant was that we were forced to sweat blood to get a decent overall grade; but when we wrote our finals (graded by other teachers), most of us in his English class got distinctions for our essays.

I have mentioned that sports was a compulsory activity in all private boys’ schools of the time, and we produced our share of decent sportsmen. But when we were up against the local state (“government”) schools, we would usually get thrashed — much as, say, Harvard’s football team would fare against Michigan or Alabama — because our two senior classes of about a hundred boys stood no chance against the same pool of a thousand boys from the much-larger King Edward’s School down the road. It didn’t matter, though; as a cheer from St. Stithian’s College went, whenever they were beaten by a government school: “Your dads work for our dads!”

We at St. John’s would never have been so crass, but then St. Stithian’s was a Methodist school, after all.

But even being crap at sports against other schools was instructive: learning how to lose with grace meant that we won with equal grace; and in its turn, sportsmanship was not only welcomed, but treasured. Good sportsmanship, by the way, means following not just the letter but the spirit of the rules — which is why I’m always hammering on that something may be legal, but that doesn’t make it right. (A no-class boor like Bill Clinton would never understand that, which is why he and his equally-classless wife are such terrible people. Former BritPM and Old Etonian David Cameron, while an appalling politician, is actually quite a decent man, especially when compared to the horrible Gordon Brown. The same is true of the equally-inept but privately-schooled and very likeable George W. Bush when compared to the awful Bernie Sanders.)

The Old School Tie goes deeper than that. As a rule, our dating pool was the local girls’ private schools: Roedean, St. Andrew’s, Kingsmead and St. Mary’s Schools for Girls. (I think I first seriously dated a government-school girl when I was twenty-four, and my experience was not uncommon.) Once again, it was because the girls were a known quantity: of good / wealthy families, well brought up, with ladylike and genteel manners. (Yeah, they were bitchy and obnoxious because teenagers, but it was a very ladylike obnoxiousness.) It also worked for the good. One of the Old Boys date-raped one of the Old Girls one night; word got out, and he never dated in our circle again — he ended up marrying some tart from Cape Town who didn’t know his story. The last I heard, he was miserably unhappy because he was savagely cut from the group and lost all his friends. To be called “a nasty piece of work” was pretty much a death sentence, socially speaking, and he was. The very tightness of the circle thus gave security against nonsense like that, just as it would almost guarantee that my tech-company owner friend would be inured against financial impropriety by his CFO.

So there it is: the Old School Tie, the Old Boys’ Club; call it what you may, sneer at it all you like, but the fact of the matter is that without the efforts of this tiny group of men and women over the past few centuries, society and civilization would be much the poorer.

Your opinion may vary, of course, but we don’t really care.