It is no secret among my Readers (especially those of long standing) that when it comes to decades. I have a soft spot for the 1950s.

It happens to be the decade of my birth (1954), and of course my memories of that time are scattered and few, but there’s a feeling about that era that has resonated with me pretty much all my life.

Now I understand that most people have a hankering for earlier times — “I wish I’d lived in the [x] period!” — and it’s brilliantly satirized by Woody Allen in his Midnight In Paris movie, where a modern-day young writer is transported back to what many consider one of the golden ages and places of writing and the arts: Paris of the 1930s, where Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and others of that ilk are the celebrities du jour, and the many soirees at Gertrude Stein’s apartment host them plus other luminaries such as Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso and Luis Buñel. Of course, to our young protagonist, this seems to be the best time to be alive and writing, or being creative in any field. Then he meets a young woman — a struggling fashion designer — and when the two of them are magically transported back to fin-de-siècle Paris, she astonishes him by saying that she, a creature of the 1930s, would want to live in that time and not the 1930s, because she would perhaps be more successfu lback then rather than in the age of Coco Chanel.

So I’m aware of that longing, and I understand its pitfalls when it comes to talking about the 1950s as my beau ideal. Indeed, several Readers have taken me to task, outlining the many evils and perils of the 1950s — the relatively poor medicines available (compared to our modern ones), endemic racism, Puritanical social mores and so on.

And yes, I know that the technology, such as it was, was certainly inferior to ours today, whether it be telephones, cars, medicine or whatever. Nobody would want to go back to that, for sure.

But that’s not the root of my nostalgia.

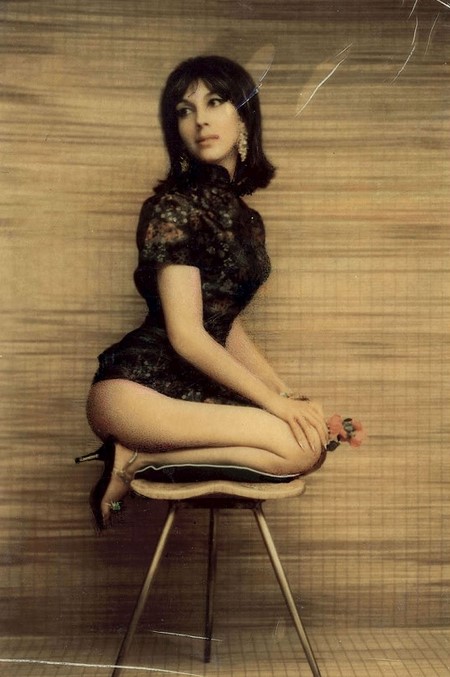

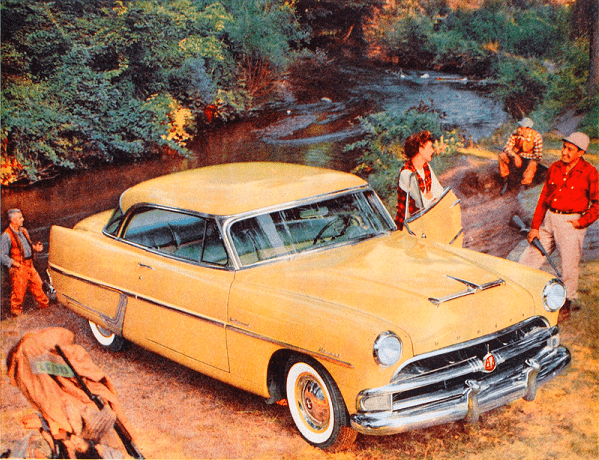

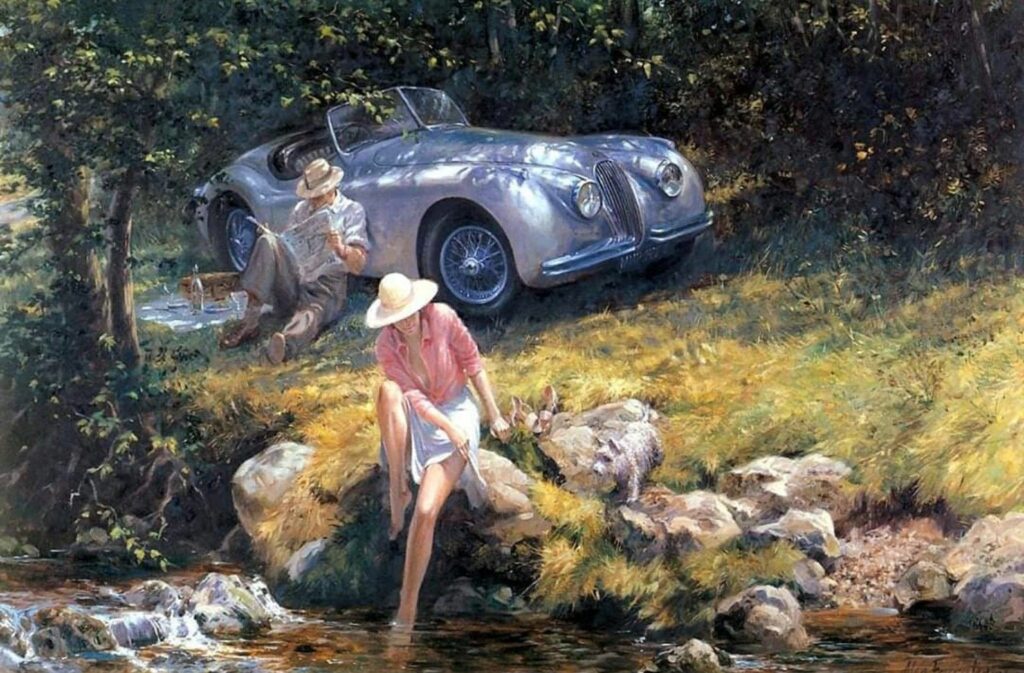

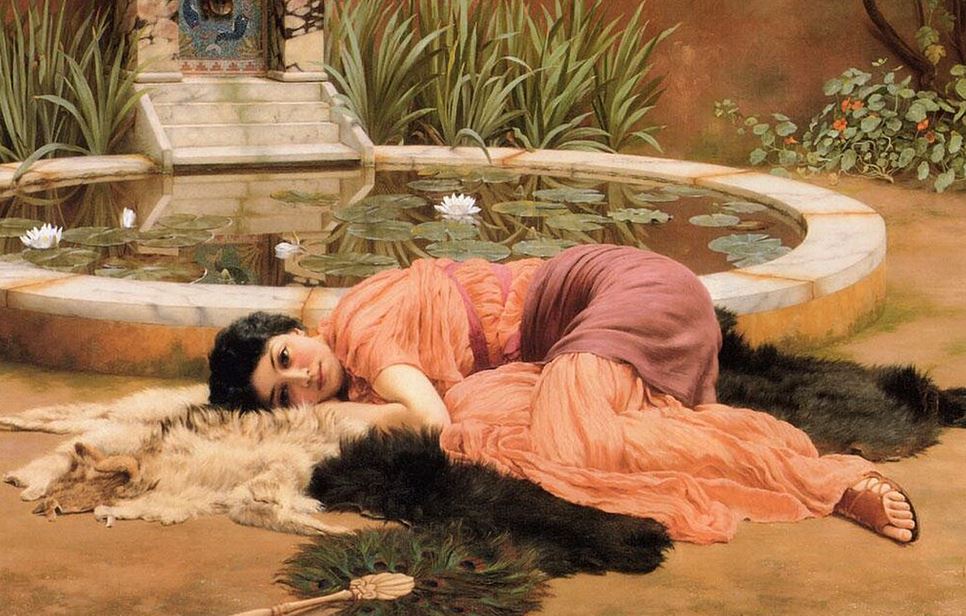

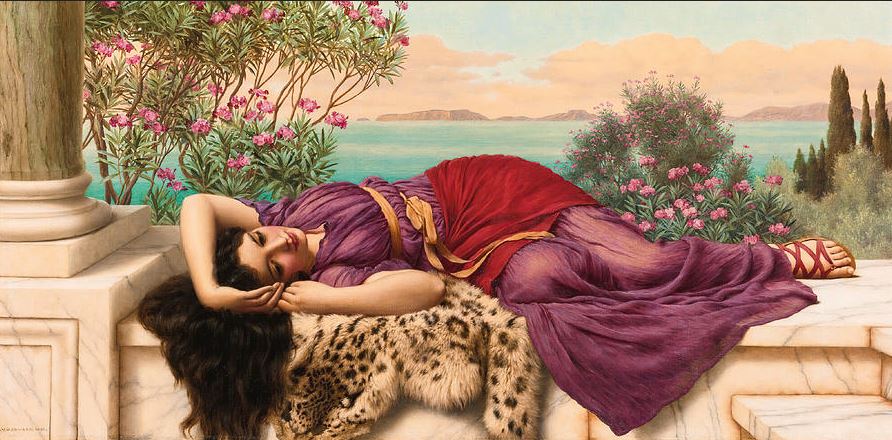

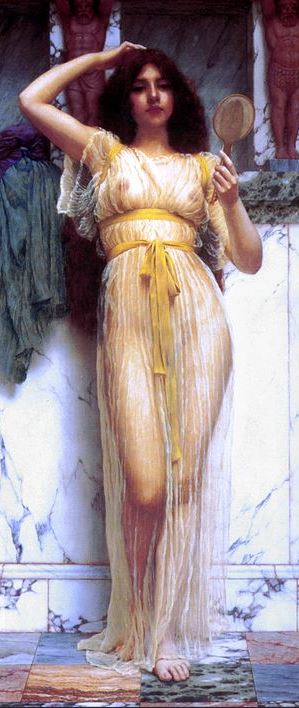

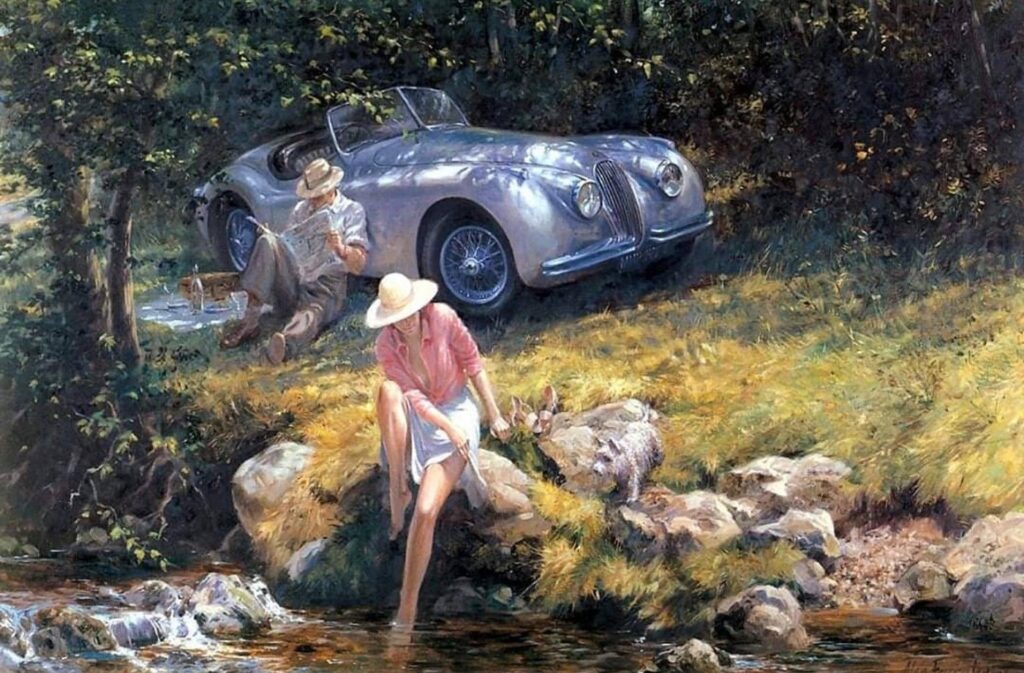

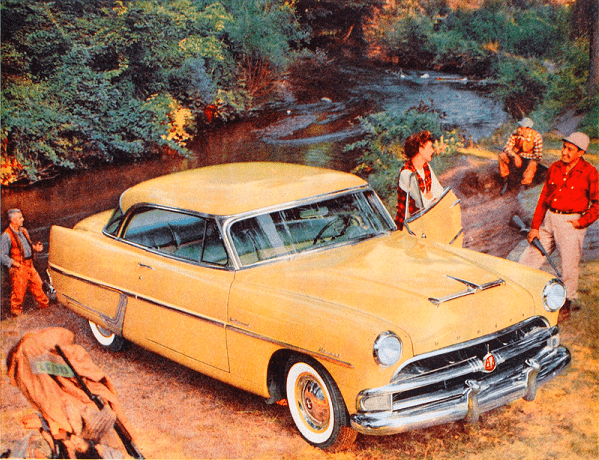

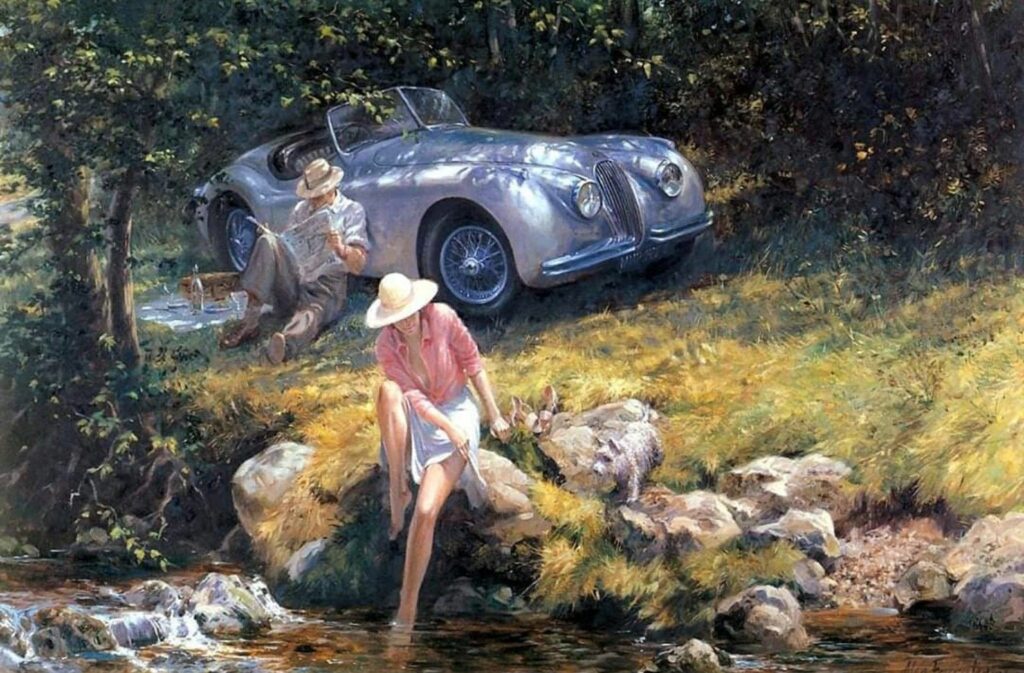

Let’s just look at a few images of 50s-as-golden-age art to illustrate my point:

Note the simplicity of life thus portrayed: a family hunting outing, a picnic for two, and a family picnic.

I’ve written about the 1950s over the years, and here are a couple examples thereof:

I have no idea, for example, how to lower the cost of living to, say, 1950s-era levels where a family of four can live in a reasonably-modest dwelling, own one or two inexpensive cars, have enough to eat, and afford to give the kids a decent education — all on one salary, at a stable place of employment. In order to get there, we’d have to make drastic changes to our national way of life, changes that I’m pretty sure that nobody would want to make.

As a comment to Cappy’s excellent take on returning to the 1950s:

Don’t expect the world to revert to the 1950s ethos. In fact, as Cappy points out, modern society is being taught that the 1950s were a bad time because racism / McCarthyism / Cold War nuclear holocaust / oppressed women etc. What’s being omitted from the indoctrination is its purpose, which is to undermine what made the 1950s great: patriotism, a sense of honor, hard work, deferred gratification, strong family ties, Judeo-Christian morality, modest living and so on.

And:

I’m often teased by my friends (and on occasion by my Readers) for being so unashamedly old-fashioned about life, and the things and people with which we associate ourselves. To this teasing I am entirely inured, and about my attitude I am utterly unrepentant. I am a conservative man, and that’s because I believe that in our own past, and in the history of civilization, there is much worth conserving. Certainly, that is true of our recent history (the 1950s), as much or more as it is true of earlier decades and even centuries.

So yes: go ahead and laugh at my nostalgia, mock my preference for times gone by, and point out all the things that were wrong with the 1950s.

With all that said, though, I still insist that there was a whole about the 1950s that wasn’t shit: the culture, the fact that the lines between right and wrong were a lot less blurred, and the roles of the man and woman a lot better defined — and we were all the better for it.

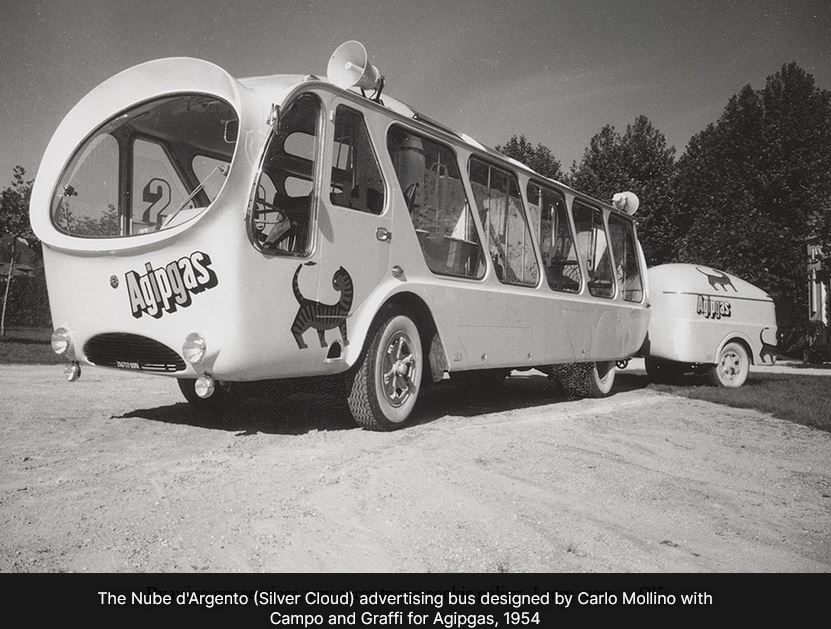

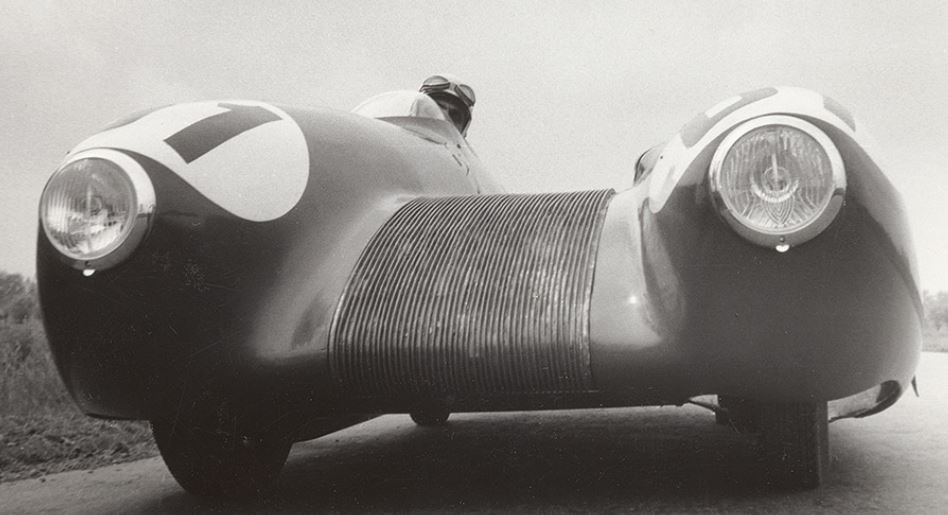

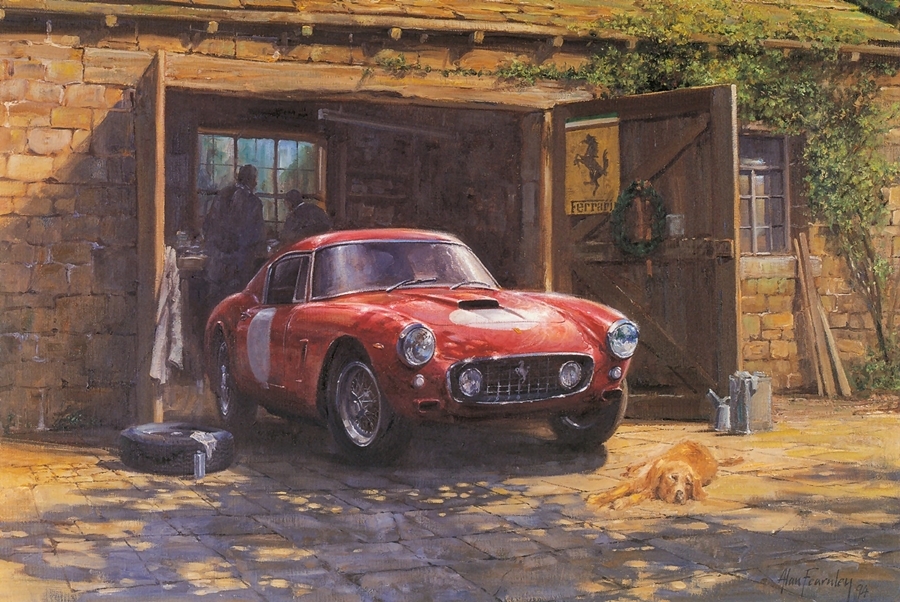

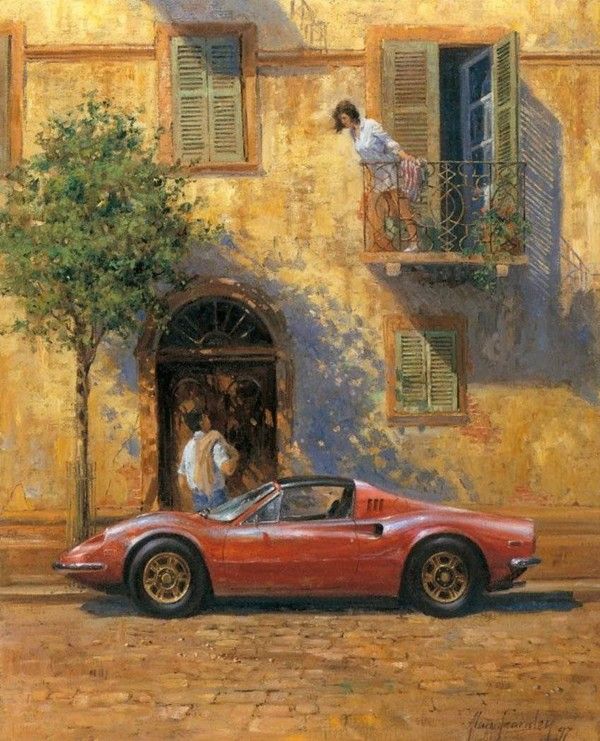

I won’t even talk about the cars…

Not much wrong there, either.