I first met Pete DiStaulo back in 1985, when I joined a small marketing company as director of their supermarket relations effort — I was, if you will, an in-house consultant to their clients who were all just starting loyalty programs. About my age, Pete was the VP of IT, and we hit it off immediately, my no-bullshit management style being a perfect match for his Jersey-City no-bullshit technical expertise. I don’t know what company management expected from our friendship, but to their consternation I was more often on his side rather than on their side, because while Pete knew next to nothing about marketing and Management knew absolutely nothing about IT systems, I knew a great deal about both, and I was able to temper their sky-high expectations of IT with the realities thereof.

Anyway, Pete and I became family friends, in that not only did he and Connie get along, but his wife Margie became part of our little IT circle.

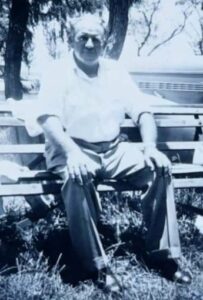

Pete was a small, tubby man with a receding hairline, while Margie was a large, overpowering woman (a senior nursing sister in a local Jersey hospital) who terrified everyone she met — her husband not excepted, she insulted and verbally abused him constantly — but both Connie and I thought she was wonderful. Connie’s genteel Beverly-Hills politeness contrasted so much with Margie’s Jersey-City brusqueness that one would have thought that they’d never get along; but we and the DiStaulos got along famously, and had dinner together more times than I can remember, more often than not causing consternation among the restaurants’ customers with our peals of helpless laughter. By the way, Margie wasn’t Italian, but Irish. “And I had to learn how to cook his fuckin’ guinea food, because he hated anything that wasn’t pasta. Jesus Christ, what a fuckin’ nightmare this marriage has been.”)

I left the marketing company after a while — hired away by one of their biggest clients to rebuild and relaunch their failing loyalty program — but Pete and I stayed close friends. In fact, when I left the supermarket company three years later to start up my own consultancy, Pete left his company to become my partner.

Time passed, and sadly, there was just not enough IT business for Pete to stay on, but even though he left to head up a local bank’s IT department, there was no rancor — in fact, we became closer friends than ever, talking on the phone at least a couple times a month and still having dinners together as a family thing.

His son Pete Jr. (“Petey”, duh) finished his college degree at Tufts and was offered a couple of jobs: one in downtown Manhattan and the other in Chicago. Amazingly (he being a Joizee boy), Petey turned down the City job for Chicago, and his move to the Windy City happened only a month or so after Connie and I moved to the lakefront.

Of course, Pete and Margie had helped Petey with his move, and when they all arrived in Chicago, needless to say we had dinner at our apartment in Lakeview. To our general astonishment, it turned out that Petey didn’t have a sofa for his new place, and we had discovered that our large sofa took up too much room in our apartment — so then and there we gave it to Petey, and he and his dad moved it over to the new apartment.

Incidentally, the Manhattan job that Petey DiStaulo had turned down? It was with Cantor Fitzgerald, on the top floor of the World Trade Center, and his start date would have been September 1, 2001. (Yeah, I got the shivers, too.)

Living across the country from each other only meant that the DiStaulos and Du Toits had fewer dinners together, but Connie was working for Ernst & Young in NJ, so every time she had to go there for a management meeting or the like, I’d go with her so we could get together with Pete and Margie, and our ongoing phone calls were frequent and needless to say, cordial.

Then Connie got ill, and Margie was distraught — as a nurse, she knew all about cancer, of course — and now she started calling Connie, often, for updates on her condition.

When Connie passed away in February 2017, of course I called Pete to tell him the tragic news, but I only got his voice mail so I just left him a message.

The next evening I got a call from his phone, but it was Margie on the line.

“Kim, I don’t know how to tell you this, but Pete passed away last November.”

“Damn Margie… why didn’t you call and tell us?”

“I couldn’t — I just couldn’t. I didn’t know how Connie would take the news, and I was afraid she wouldn’t be able to handle it.”

I thought about that for about three seconds, and said, “Margie, I don’t think she could have handled it. Pete going away might well have pushed her over the edge.”

“That’s what I was afraid of.”

“Margie, thank you for not calling us. Please don’t feel badly about it, because as hard as it is to think about, you did the right thing, I promise you.”

“Good, because the kids have been giving me no end of shit for not calling youse.”

“Margie, what happened to Pete?”

A pause, then, “That fuckin’ asshole.”

Despite myself, I started laughing helplessly. “What did he do?”

“You know he fell and busted his hip, right?”

“Yup. But I thought he was doing okay.”

“Is that what he told you?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Kim, he wasn’t doing okay, the lying little shit. He couldn’t get up the stairs, we had to convert his office (“awfiss”) to a bedroom, and he was basically bedridden for four months.”

“Ah man… so what happened?”

“Donald Trump killed him.”

“WHAT?”

“On Election Day, Pete absolutely insisted on getting out of bed, making me half-carry him to the fuckin’ car, and I had to drive him to the fuckin’ polling station so he could cast his fuckin’ vote for Donald fuckin’ Trump.”

I couldn’t say anything because I was incoherent with laughter. Which then stopped.

“And then the next day my Pete just died. The autopsy showed a pulmonary embolism that was probably caused by his being bedridden, and it was dislodged by his activity of the day before, that going to vote for Trump.”

And there you have it. Donald Trump killed my great friend Pete; well, according to his widow, anyway.

Despite her offhandedness and abuse, Margie was absolutely devoted to Pete (“Kim, he took my fuckin’ virginity!“), and he to her. Of course, it was easy to see why, because they were the most warm and wonderful people I have ever been privileged to meet.

Of course, no prizes for guessing what triggered this reminiscence from me.

I wonder if Margie voted for Trump, this time round… I’d give her a call, but a couple years after Connie died, my last attempt met a “no longer in operation” tone, and Margie too disappeared from my life.

I miss the DiStaulos, terribly.