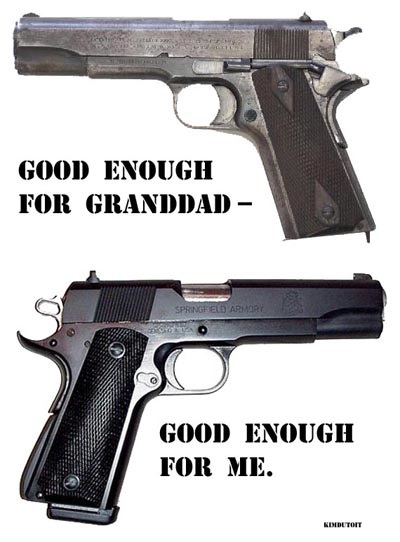

Although I have something of a reputation for being a gun nut, I’m more of an admirer than an aficionado. Sure, I can tell the difference between most older bolt-action rifles with just a brief inspection (because that’s a particular passion of mine), but the model numbers of the various Glock, SIG and S&W guns leave me cross-eyed with confusion. Unless I actually own or want a particular model, I have little interest in its stablemates, clones, extensions or forerunners.

When it comes to things aeronautical, I’m likewise not one of those obsessive types who can tell at a glance the difference between a Spitfire Mk.III or Mk.IX, but my goodness, I do love the shape of the things:

One of the very few regrets of my life is that apart from puttering around with a friend’s ultralight, I never learned to fly and get my PPL, because I would love to have taken a WWII-era fighter aircraft for a quick flight. Even the much-maligned Hawker Hurricane has not escaped my gaze:

The great WWII flying ace Douglas Bader flew both in action during the Battle of Britain, and his comment was that while he loved the agility and performance of the Spit, he grew to appreciate the Hurri as a rock-solid gun platform that could withstand an incredible amount of punishment — even though its rear fuselage was made entirely of canvas-covered wood.

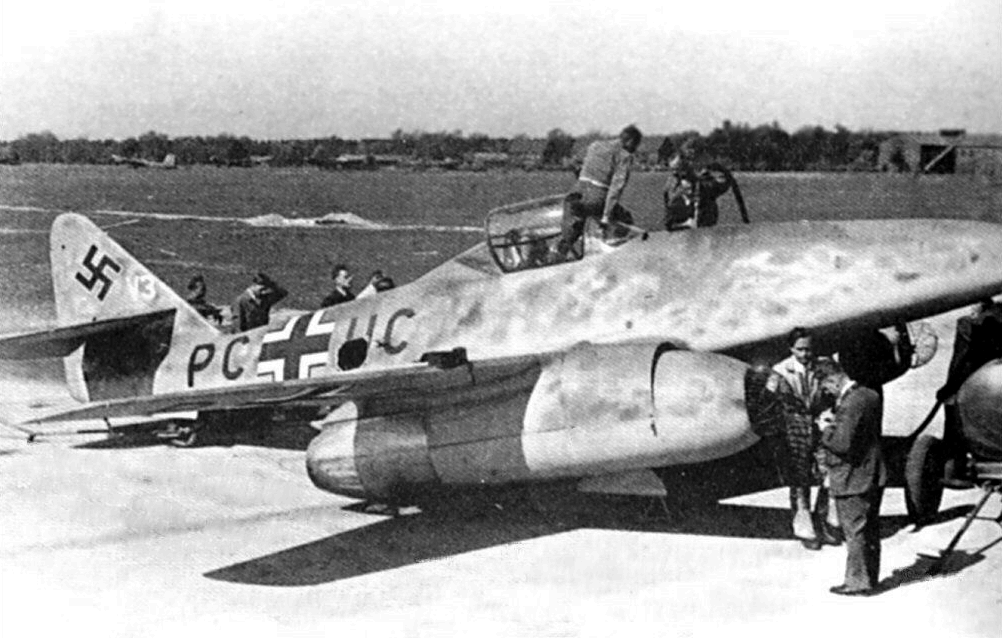

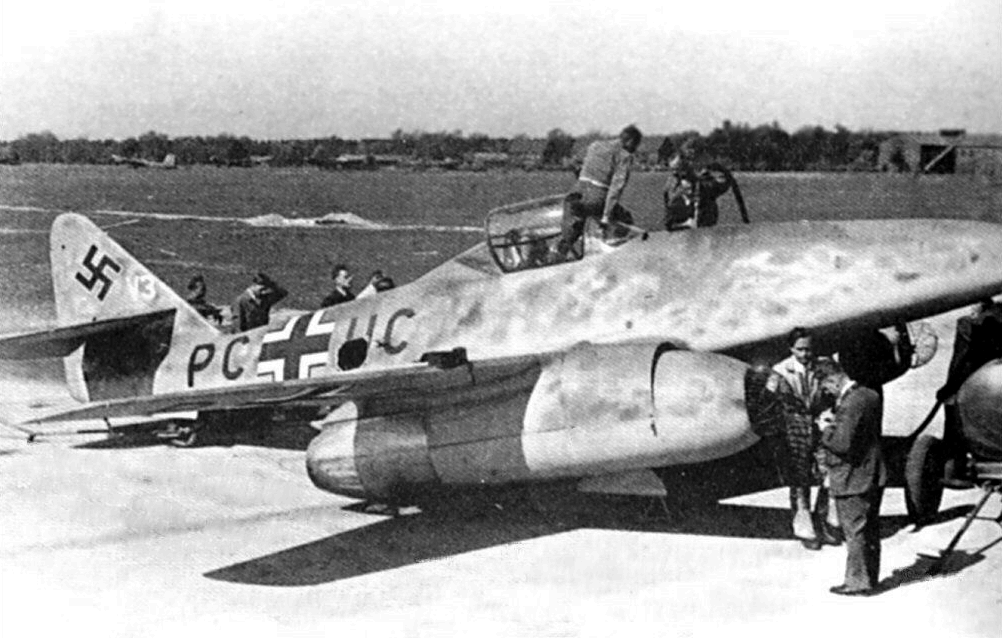

I’ve seen a Spitfire in the flesh, as it were, as well as its major opponent, the Messerschmitt Bf 109, as both were displayed at the War Museum in Johannesburg.

What struck me then, as now, is how small those wonderful aircraft are. Also at the museum was one of the few remaining Me 262 jet aircraft, and by comparison to the dainty 109, it was a great hulking brute of a thing:

…although I have to tell you, that shark-like fuselage has its own particular attraction for me too.

As a boy, I was fascinated by WWII fighter aircraft and built models of almost all of them: Spitfire, Hurricane, P-51 Mustang, Me 109; you name it, I probably built it. As I’ve aged, I’ve tried to understand just what it is that attracted me (and still does to this day) to these aircraft, and I think I’ve finally figured it out.

These were not the fragile, unreliable and dangerous aircraft of WWI, nor are they the techno-laden jet fighters of the post-WWII era. Instead, they were flying machines which made you feel like you were part of a miracle. The speeds were nowhere close to supersonic (a modern-day Bugatti Veyron has a top speed just 100mph slower than that of a 1939 Hurricane), and honestly, I think my criterion for these WWII fighter planes is one of enjoyment: you’re going fast, but not that fast that you have no time to think about the experience. Kind of like the difference between, say, a Caterham 7 and a Pagani Zonda.

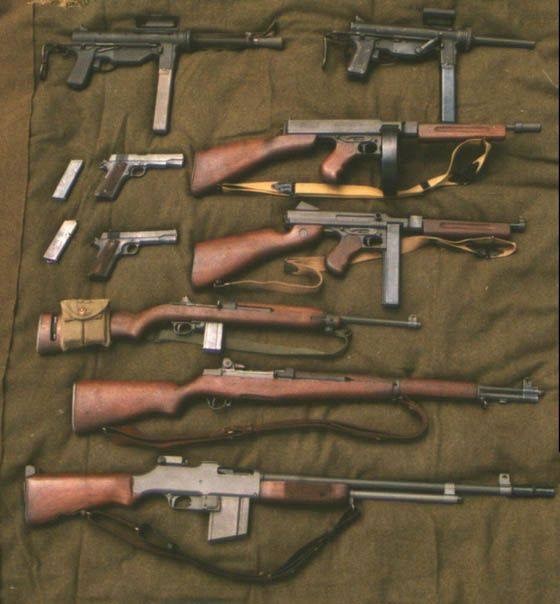

I like both, but I’d rather drive a Caterham than a Zonda for the same reason that I prefer a bolt-action rifle to a full-auto rifle: there’s more of an element of actively making the 7 and the turnbolt work, rather than just controlling the Zonda and (say) a BAR. Speed has little to do with it, although I suspect that the thrill of speed in a Caterham may be every bit as good as in a Zonda, even though the latter may be going half as fast again as the 7. Fast is fast: what’s the difference is how much one can feel it — and I suspect that without a speedometer to tell you the difference, you might not be able to quantify it that much.

So give me a good old WWII aircraft — the aeronautical equivalent of the Caterham — any day of the week.

And to quote a friend in a different context: when I see a pic like this one, parts of me start to tingle that haven’t tingled in a long while.

Can you imagine the sound those nine Merlin-engined beauties make as they thunder overhead? I don’t smoke, but I’m pretty sure I’d want a cigarette after that flyover.