Question from Reader JockC, via email:

“Did you own any other rifles back in South Africa, or was the Israeli Mauser the only one?”

Getting one gun in those days was relatively easy. As I recall, the license application for the Llama pistol took about a month to be granted, and the Mauser only a matter of weeks. “Self-protection” for the handgun required a background check, but “hunting” and a bolt-action rifle was hardly even scrutinized, as far as I can tell.

Getting your second gun always took longer, as the “Why do you need another gun?” had to be justified, and “Because” wasn’t acceptable. Once again, the hunting thing was much easier, especially if one was applying for a larger- or smaller-caliber chambering. A second handgun, unless for a specific sporting purpose, like a target pistol? Oy. It could take as long as a year for the license to be granted. So I only ever owned one handgun at a time, as did many of us.

Officially, that is.

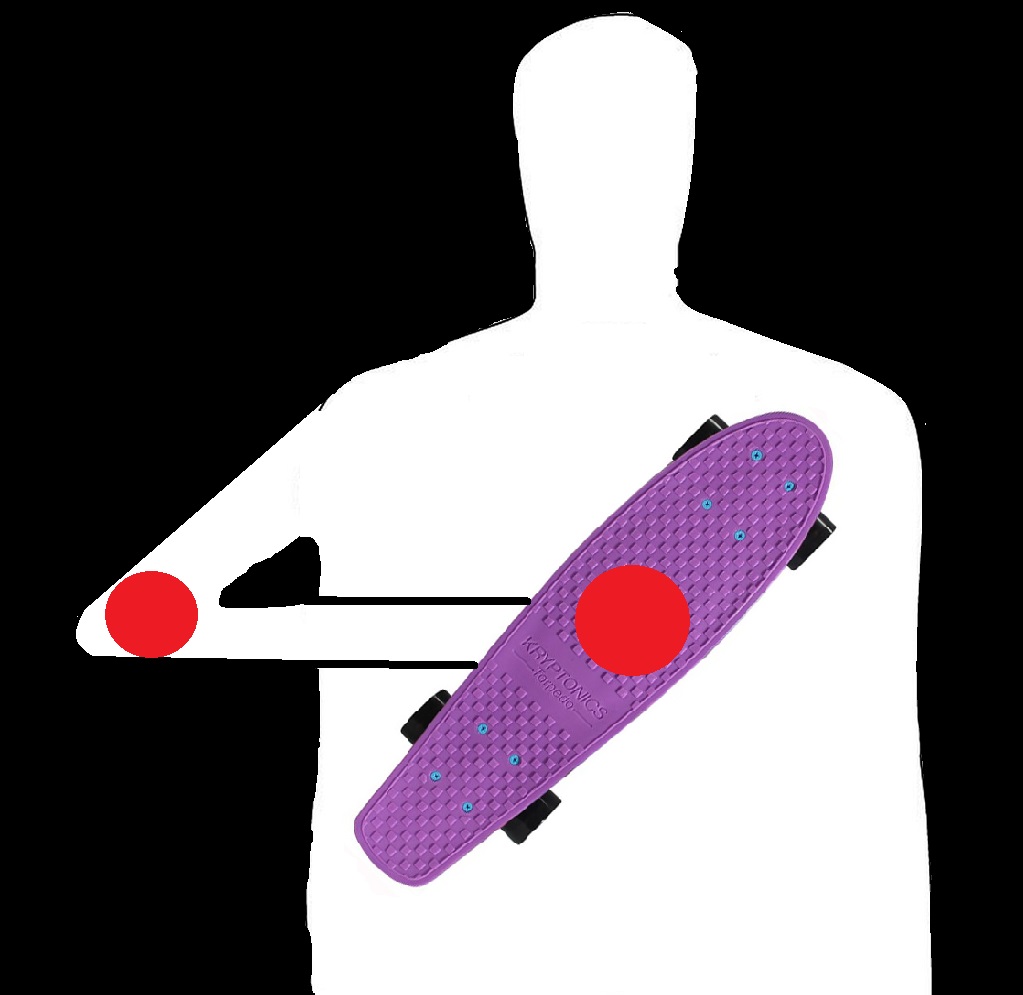

The only other centerfire rifle I owned back in the old Racist Republic was an Oviedo Spanish Mauser in 7x57mm, similar to the one below except that I had the bolt altered so I could use a scope with the thing.

I have spoken many times before of my affection for the old, gently-recoiling cartridge, seen here alongside the other popular ones in use at the time:

The long bullet of the 7×57 allowed for astounding penetration, which often made a “quartering” shot as deadly as a side-on shot.

The Orviedo Mauser was the Model 1893 (similar to the “Boer” Mauser of later fame), and many was the approving nod I got from Oom (uncle) Sarel and his farmer friends whenever I uncased it.

This was the gun I used for almost all my hunting (a.k.a. poaching), and it was never registered to me under S.A. law because reasons. (I did occasionally use borrowed rifles, but the Spanish Mauser was the main one.) I got it from the estate of an acquaintance who’d been killed in a car accident, and whose father just wanted to get rid of it.

Using the unregistered gun instead of the Izzy (which was registered to me), I had no compunction about tossing it into a ditch should the game rangers ever appear… but fortunately that never happened. Just before I emigrated, I gave it to the farmer on whose farm I did all my hunting out in the Northern Cape.

As to the area where we hunted: yikes. I have no pictures of where I hunted, nor any trophy pictures, because under the conditions I hunted, those could be called “evidence” and used against me. But I found some pictures of the terrain up in the northern Cape Province (as it was back then), and they should give you a glimpse of conditions along the fringes of the Kalahari Desert:

Dry as hell, hot as hell, no place for White men (as the saying goes) and only mad dogs and Englishmen etc. etc.

Despite the harsh conditions, game was relatively plentiful, although we usually only hunted for culling purposes — such as when a springbok herd started grazing on pastures meant for sheep or cattle, and had to be made to fear the area. I myself grazed on springbok biltong for about six months after that occasion. Then there were the lions, who just followed the game onto the farm, and had to be dealt with, in the words of the farmer, “so they don’t develop a taste for beef, sheep and humans.”

I would get an evening call from Oom Sarel the farmer: “Neef (nephew) Kim, do you feel like a bit of shooting this weekend?” and if I was free, I’d load up the car and set off before midnight Friday for the six-hour drive out to Kuruman, the nearest town.

I enjoyed it immensely, as much as for the companionship of those weekend hunts as for the actual hunting. What I learned from those outings was that I wasn’t as good a shot as the farmers — hell, the neighbor’s 17-year-old was death on wheels, and when he shot, he worked his rifle’s bolt so fast it sounded more like semi-auto fire. (It was a Sauer .270 Win, I think, but I do remember that his one-shot kill ratio was well over 75%. Astounding.)

Anyway, that’s the story of my hunting days. There were a couple others, in different areas, but those weren’t as illicit, nor as enjoyable, as the ones out on Oom Sarel’s farm.

Side note: In South Africa, younger people address their elders as “oom” (uncle) or “tannie” (auntie) out of respect, even when not related. In return, the older folks will call the younger ones “neef” (nephew), “seun” (son) or “dogter” (daughter) and “niggie” (niece). It is a very affectionate and respectful custom, and I have to admit that I miss it.

The Afrikaans “g” is pronounced the same as the Scottish “ch” as in “loch”.