Longtime Reader Newt F sends me the following question:

Yesterday I was online and followed a link to “Top Gun Blogs,” and I was surprised that you weren’t even in the Top 50. Given that a lot of your readers (including me) would think that you should be, why is that?

Thankee for the compliment, but I don’t think that I can call myself a “gun blogger” anymore, and probably lost the appellation when I switched over from the Nation of Riflemen to The Other Side Of Kim; and certainly, this latest manifestation of mine, Splendid Isolation, is even further away.

Although if you click on “The Gun Thing” category on the right hand side of this page, you will find over 90 pages of gun-related posts (about five posts per page, good grief), it’s worth noting that jokes and such (“Funny Stuff”), cars (“Drive Time”) and booze/food (“Food & Drink”) have 80, 30 and 23 pages respectively. Clearly, there’s a lot more than just guns over here, nowadays.

More to the point: volume doesn’t count as much as quality, and I’m not sure that my recent fevered scribblings about guns are even close to the quality of some of my earlier gunny posts.

None of this matters, of course. I have no interest in popularity, nor recognition of my writings. I write for myself, on topics which interest me, and any following I may accrue in so doing is simply a happy concidence.

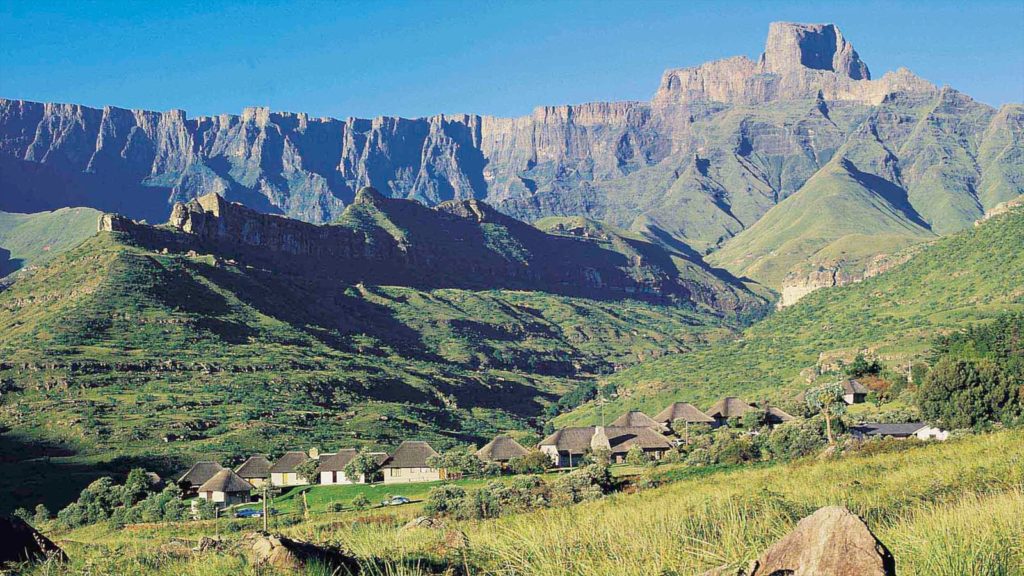

And you’re all welcome on this back porch of mine. Just mind yer manners, handle yer guns with respect, don’t spit baccy juice on the floor, and all will be well.

Cheers, y’all…