The day after my Lord’s pilgrimage, Mr. FM suggested we take a quiet drive into the Cotswolds, some few miles north-west of FM Towers. He knows that I’m not one for scenic drives just for the drive’s sake, so he mentioned the magical words “in the Porsche” — and needless to say, that was sufficient incentive for me to agree.

So we footled around along English country roads — me oohing and aaahing at Teh Scenery, which is spectacular: rolling hills, forest glades, farmers doing Farming Things, etc. Of course, it being a lovely day (sunny, warm, bees buzzing lazily etc.) there were the usual problems (i.e. cyclists), but the oncoming roar of a 3.6-liter Porsche engine usually had the desired effect of sending them flying into roadside ditches, which is all part of the fun of a summer drive. Then things took a turn for the worse. Much worse.

We turned off the country road onto what can best be described as a farm road and ended up at a series of farm-type buildings. Over the door of one such building was a sign which read, cryptically, “R.J. Blackwall”. What place is this, I wondered, and then we went inside.

Rupert Blackwall is one of the pre-eminent Mauser dealers in the British Isles.

O My Readers, I need first to give you a teeny bit of background so you can fully appreciate what was to follow. In the Great Time Of Poverty when I was forced to sell almost all my guns, I found myself, for the first time in my life, Mauserless. Never mind Mauser lookalikes or derivatives thereof; ever since I can remember, I’ve had at least one actual Mauser rifle in my gun cabinet — in fact, my very first gun purchase in the U.S. was a Mauser 98K. Since the Great Poverty, some four years ago, I’ve been without a Mauser — a fact I’d once lamented to Mr. FM, en passant — and only now did his devilment come to light. You see, he’d seen my reaction to the exquisite M12 I’d fired only a week before at the Corinium range and thus, I believe, had schemed a visit to this… this temple to Vulcan’s Dark Arts.

Of course, that’s not how he played it, the foul man; he chatted with Mr. Blackwall — a gunsmith of considerable skill and knowledge, having been trained at E.J. Churchill — about some rifle he was considering for his next African safari, leaving me to wander around the store and browse among (actually, drool over) the store’s wares.

First I saw a matched pair of AyA 20-gauge side-by-side shotguns (which I will need for future High Bird Shooting excursions), but I knew that the cost thereof was going to be silly: and in pounds sterling, still more so. With a deep sigh, I moved on. Until I came to the “second-hand” rack…

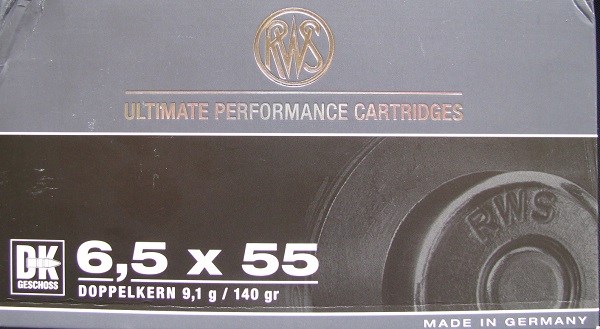

..and there it was: a barely-fired Mauser M12, in… 6.5x55mm (my favorite medium caliber of all), at a price that, when translated into U.S. greenbacks, was not expensive at all. In fact, it was… affordable.

Of course, one can’t just buy a rifle and walk out of the door with it, not in Merrie Olde England, oh no. In fact, I thought that I would not be able to purchase any gun, because (as we all know) in the U.S. such things are streng verboten (as I’d discovered when first I emigrated and wanted to buy a gun). Well, no. In the U.S., not anyone can buy a gun, but anyone can own a gun (mostly). In Britain, it’s the reverse. I could buy the gun, but I couldn’t take possession of it — it would have to go onto a British gun owner’s license — until such time as I would leave the U.K. And of course, standing right next to me, with an evil leer on his aristocratic features, there was just such a British gun owner.

All that remained was to give Mr. Blackwall my credit card.

I’ll be “testing” it over the coming weeks at Corinium, once I get a decent scope on it. Range report(s) and pics to follow.

And most important of all, I am no longer Mauserless, so all my old Boer forefathers can stop spinning in their graves.